Picking the Right 3D Laser Scanning Technology for Your Company Needs

The globe of 3D laser scanning is large and complex, using a myriad of opportunities for organizations in different sectors. 3D Laser Scanning: The Future of Sustainable Dallas Development . From design and engineering to construction and manufacturing, this cutting-edge technology has the potential to reinvent the means companies run and supply results. Nevertheless, with such a wide variety of alternatives available, selecting the suitable 3D laser scanning technology can be a complicated job, specifically for those brand-new to the field.

Below are some vital aspects to think about when selecting the ideal 3D laser scanning technology for your organization requirements:

Function and Application: Prior to diving right into the globe of 3D laser scanning, its crucial to identify the details demands of your service. Are you wanting to develop in-depth topographic maps for a construction project? Do you need accurate point clouds for reverse engineering? Comprehending your objective will certainly help narrow down your choices and guarantee you invest in a technology that satisfies your needs.

Accuracy and Resolution: The accuracy and resolution of the scanner are vital elements to take into consideration. If your business needs exact dimensions and detailed information, you might need a scanner with high-resolution capabilities. On the various other hand, if your needs are less demanding, a more budget friendly lower-resolution scanner may be sufficient.

Range and Rate: The scanning range and rate of the technology are likewise important considerations. If youre working with large-scale projects or need to cover considerable locations, youll desire a scanner with a long array and high scanning rate. On the other hand, if your projects are smaller sized in scale, a scanner with a much shorter array yet high precision could be better.

Portability and Alleviate of Usage: Depending on your service procedures, you may require a scanner that is mobile and very easy to use in the area. Some 3D laser scanning modern technologies are developed to be handheld and straightforward, while others are extra fixed and complex. Think about the needs of your workforce and the atmosphere in which the scanner will be utilized.

Cost and ROI: While 3D laser scanning technology can be a considerable financial investment, its essential to think about the lasting advantages and potential return on investment (ROI). Premium scanners might feature a large price, however they can likewise supply considerable enhancements in precision, efficiency, and data quality. Its critical to consider the expense versus the potential cost savings and boosted end results that the technology can give.

Software Compatibility: Numerous 3D laser scanning innovations come with exclusive software

Unlocking the Power of 3D Laser Scanning for Your Dallas Business

In todays busy company atmosphere, staying in advance of the contour often means embracing cutting-edge innovations. For services in Dallas, 3D laser scanning uses a transformative opportunity to enhance efficiency, precision, and advancement throughout different industries. Applying 3D laser scanning successfully, nevertheless, requires a strategic approach based in best methods and mindful factors to consider. By comprehending these, Dallas organizations can fully leverage this technology to acquire a competitive edge.

3D laser scanning, or LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging), is a technology that records specific dimensions of physical spaces and objects by using laser light to produce detailed 3D models. This technology is invaluable for a variety of applications, from construction and architecture to manufacturing and logistics. The benefits are various: it substantially reduces the time and labor associated with data collection, decreases errors compared to traditional methods, and gives a digital twin of physical rooms that can be utilized for planning, analysis, and simulation.

To apply 3D laser scanning effectively, organizations need to first plainly define their goals. Recognizing the particular objectives-- whether its enhancing accuracy in construction projects, enhancing product design procedures, or optimizing warehouse area-- will certainly assist the selection of equipment and software, making sure alignment with business demands.

Selecting the best equipment is another crucial consideration. The marketplace uses a selection of 3D laser scanners, each with different capacities and price factors. Variables such as the degree of information needed, the dimension of the area to be checked, and the environment in which the scanner will be used ought to affect this decision. For example, a high-precision scanner could be essential for in-depth architectural work, while a more sturdy model might be far better fit for outdoor construction websites.

Training and competence are just as important. The intricacy of 3D laser scanning technology necessitates skilled drivers that can take care of the equipment and software properly. Investing in training for staff or working with specialists can make sure that data is caught precisely and that the full capacity of the technology is realized. Additionally, ongoing training can assist groups remain upgraded on new functions and ideal techniques.

Data management is another vital consideration. The substantial quantities of data created by 3D laser scanning call for robust storage solutions and reliable data processing capacities. Services ought to develop methods for data managing, consisting of storage, backup, and security, to secure sensitive information and guarantee data integrity. Cloud-based solutions can use scalable storage options and assist in collaboration among teams.

Integration with existing systems is likewise

Integrating 3D laser scanning data with existing systems and operations can revolutionize the way Dallas services run, using boosted precision, efficiency, and development. As technology continues to advance, companies across numerous sectors are acknowledging the tremendous possibility that 3D laser scanning brings to their operations. Texas commercial 3D scanning brings Lone Star-sized precision to your portfolio. Nonetheless, to genuinely open its power, seamless integration with present systems is crucial.

Among the primary benefits of 3D laser scanning is its ability to capture highly precise spatial data. For businesses in fields like design, construction, and manufacturing, this indicates having accessibility to in-depth models that can enhance design precision and task planning. By integrating this data with existing CAD (Computer-Aided Design) and BIM (Building Information Modeling) systems, companies can simplify their operations, minimizing the time and effort required to transition in between different stages of a task. This not just increases project timelines but additionally decreases the risk of errors, causing higher quality results.

Furthermore, integrating 3D laser scanning data with enterprise resource planning (ERP) and task management devices can boost overall operational efficiency. For example, in the construction industry, real-time data from laser scans can be fed straight into

In todays affordable service setting, optimizing roi (ROI) is vital for development and sustainability. For organizations in Dallas seeking to enhance their operations and improve processes, including 3D laser scanning technology can be an incredibly efficient strategy. This advanced method not just assures precision yet likewise supplies significant cost-benefit benefits that can significantly improve your ROI.

In the beginning glance, purchasing 3D laser scanning might seem like a substantial in advance expense. Nevertheless, when we delve into the in-depth cost-benefit analysis, it comes to be clear that the long-lasting benefits far surpass these preliminary expenditures. Among the primary benefits is the extraordinary accuracy in measurement and documentation. For construction projects or facility management, this means less mistakes, less rework, and inevitably, lower expenses related to errors and ineffectiveness.

Furthermore, 3D laser scanning significantly reduces labor-intensive tasks. Instead of manual dimensions and extensive data collection, a single scan can capture thorough spatial information rapidly and accurately. This conserves time and resources, allowing your group to focus on even more tactical elements of your service, hence improving general performance.

Another critical element is boosted decision-making. With detailed and specific data available, local business owner and project supervisors can make enlightened choices based on real-time, accurate information as opposed to price quotes or obsolete data. This not just reduces risk but also accelerates task timelines, directly influencing your bottom line favorably.

Moreover, incorporating 3D laser scanning right into your organization processes can bring about enhanced client complete satisfaction and competitive advantage. Customers appreciate openness and precision, qualities that are considerably improved by utilizing such advanced innovations. This can result in repeat organization and references, properly improving your company's track record and profits.

Lastly, it is essential to take into consideration the durability and flexibility of 3D laser scanning systems. As your organization grows and projects progress, these devices can quickly scale and adapt to brand-new demands, ensuring that your financial investment continues to be important with time.

To conclude, while the preliminary expense of executing 3D laser scanning technology may appear high, the thorough cost-benefit analysis exposes that it provides substantial long-lasting returns. From boosted accuracy and efficiency to far better decision-making and boosted customer connections, this technology outfits Dallas companies with devices to open considerable benefits and maximize their ROI. Spend wisely in 3D laser scanning, and see your service grow.

|

Dallas

|

|

|---|---|

|

City

|

|

|

Downtown Dallas

State Fair of Texas

Southern Methodist University

Winspear Opera House

Perot Museum

American Airlines Center

UT Southwestern Medical Center

Margaret Hunt Hill Bridge

JFK Memorial

|

|

Flag

Seal

|

|

| Nicknames:

Big D, D-Town, Triple D, 214

|

|

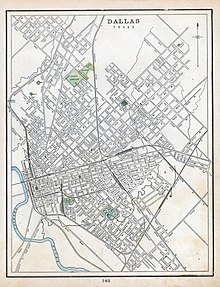

Interactive map of Dallas

|

|

Dallas

Location in Texas

|

|

| Coordinates: 32°46′45″N 96°48′32″W / 32.77917°N 96.80889°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Texas |

| Counties | Dallas, Collin, Denton, Kaufman, Rockwall |

| Incorporated | February 2, 1856 |

| Government

|

|

| • Type | Council–manager |

| • Body | Dallas City Council |

| • Mayor | Eric Johnson (R) |

| Area

[1]

|

|

|

• City

|

385.9 sq mi (999.2 km2) |

| • Land | 339.604 sq mi (879.56 km2) |

| • Water | 43.87 sq mi (113.60 km2) |

| Elevation

[2]

|

482 ft (147 m) |

| Population

(2020)[3]

|

|

|

• City

|

1,304,379 |

|

• Estimate

(2024)

|

1,304,238 |

| • Rank | 21st in North America 9th in the United States 3rd in Texas |

| • Density | 3,400/sq mi (1,300/km2) |

| • Urban

[4]

|

5,732,354 (US: 6th) |

| • Urban density | 3,281.5/sq mi (1,267.0/km2) |

| • Metro

[5]

|

7,637,387 (US: 4th) |

| Demonym | Dallasite |

| GDP

[6]

|

|

| • Metro | $688.928 billion (2022) |

| Time zone | UTC−06:00 (Central) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−05:00 (Central) |

| ZIP Codes |

ZIP Codes[7]

|

| Area codes | 214, 469, 945, 972[8][9] |

| FIPS code | 48-19000[10] |

| GNIS feature ID | 2410288[2] |

| Website | dallascityhall.com |

Dallas (/ˈdælÉ™s/ ⓘ) is a city in the U.S. state of Texas and the most populous city in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, the most populous metropolitan area in Texas and the fourth-most populous metropolitan area in the United States at 7.5 million people.[11] It is the most populous city in and seat of Dallas County with portions extending into Collin, Denton, Kaufman, and Rockwall counties. With a 2020 census population of 1,304,379, it is the ninth-most populous city in the U.S. and the third-most populous city in Texas after Houston and San Antonio.[12][13] Located in the North Texas region, the city of Dallas is the main core of the largest metropolitan area in the Southern United States and the largest inland metropolitan area in the U.S. that lacks any navigable link to the sea.[a]

Dallas and nearby Fort Worth were initially developed as a product of the construction of major railroad lines through the area allowing access to cotton, cattle, and later oil in North and East Texas. The construction of the Interstate Highway System reinforced Dallas's prominence as a transportation hub, with four major interstate highways converging in the city and a fifth interstate loop around it. Dallas then developed as a strong industrial and financial center and a major inland port, due to the convergence of major railroad lines, interstate highways, and the construction of Dallas Fort Worth International Airport, one of the largest and busiest airports in the world.[14] In addition, Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART) operates rail and bus transit services throughout the city and its surrounding suburbs.[15]

Dominant sectors of its diverse economy include defense, financial services, information technology, telecommunications, and transportation.[16] The Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex hosts 23 Fortune 500 companies, the second-most in Texas and fourth-most in the United States,[17][18] and 11 of those companies are located within Dallas city limits.[19] Over 41 colleges and universities are located within its metropolitan area, which is the most of any metropolitan area in Texas. The city has a population from a myriad of ethnic and religious backgrounds and is one of the largest LGBT communities in the U.S.[20][21]

Indigenous tribes in North Texas included the Caddo, Tawakoni, Wichita, Kickapoo and Comanche.[22][23][24] Spanish colonists claimed the territory of Texas in the 18th century as a part of the Viceroyalty of New Spain. Later, France also claimed the area but never established much settlement. In all, six flags have flown over the area preceding and during the city's history: those of France, Spain, and Mexico, the flag of the Republic of Texas, the Confederate flag, and the flag of the United States of America.[25]

In 1819, the Adams–Onís Treaty between the United States and Spain defined the Red River as the northern boundary of New Spain, officially placing the future location of Dallas well within Spanish territory.[26][page needed] The area remained under Spanish rule until 1821, when Mexico declared independence from Spain, and the area was considered part of the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas. In 1836, Texians, with a majority of Anglo-American settlers, gained independence from Mexico and formed the Republic of Texas.[27]

Three years after Texas achieved independence, John Neely Bryan surveyed the area around present-day Dallas.[28] In 1839, accompanied by his dog and a Cherokee he called Ned, he planted a stake in the ground on a bluff located near three forks of the Trinity River and left.[29] Two years later, in 1841, he returned to establish a permanent settlement named Dallas.[30] The origin of the name is uncertain. The official historical marker states it was named after Vice President George M. Dallas of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. However, this is disputed. Other potential theories for the origin include his brother, Commodore Alexander James Dallas, as well as brothers Walter R. Dallas and James R. Dallas.[31][32] A further theory gives the ultimate origin as the village of Dallas, Moray, Scotland,[b] similar to the way Houston, Texas, was named after Sam Houston, whose ancestors came from the Scottish village of Houston, Renfrewshire.

The Republic of Texas was annexed by the United States in 1845 and Dallas County was established the following year. Dallas was formally incorporated as a city on February 2, 1856.[14] In the mid-1800s, a group of French Socialists established La Réunion, a short-lived community, along the Trinity River in what is now West Dallas.[33]

With the construction of railroads, Dallas became a business and trading center and was booming by the end of the 19th century. It became an industrial city, attracting workers from Texas, the South, and the Midwest. The Praetorian Building in Dallas of 15 stories, built in 1909, was among the first skyscrapers west of the Mississippi and the tallest building in Texas for some time.[34] It marked the prominence of Dallas as a city. A racetrack for thoroughbreds was built and their owners established the Dallas Jockey Club. Trotters raced at a track in Fort Worth, where a similar drivers club was based. The rapid expansion of population increased competition for jobs and housing.

In 1910, a white mob of hundreds of people lynched a black man, Allen Brooks, accused of raping a little girl. The mob tortured Brooks, then killed him at the downtown intersection of Main and Akard by hanging him from a decorative archway inscribed with the words "Welcome Visitors". Thousands of Dallasites came to gawk at the torture scene, collecting keepsakes and posing for photographs.[35][36]

In 1921, the Mexican president Álvaro Obregón along with the former revolutionary general visited Downtown Dallas's Mexican Park in Little Mexico; the small park was on the corner of Akard and Caruth Street, site of the current Fairmont Hotel.[37] The small neighborhood of Little Mexico was home to a Latin American population that had been drawn to Dallas by factors including the American Dream, better living conditions,[38] and the Mexican Revolution.[39] Despite the onset of the Great Depression, business in construction was flourishing in 1930. That year, Columbus Marion "Dad" Joiner struck oil 100 miles (160 km) east of Dallas in Kilgore, spawning the East Texas oil boom. Dallas quickly became the financial center for the oil industry in Texas and Oklahoma.[40]

During World War II, Dallas was a major manufacturing center for military automobiles and aircraft for the United States and Allied forces. Over 94,000 jeeps and over 6,000 military trucks were produced at the Ford plant in East Dallas.[41] North American Aviation manufactured over 18,000 aircraft at their plant in Dallas, including the T-6 Texan trainer, P-51 Mustang fighter, and B-24 Liberator bomber.[42]

On November 22, 1963, United States President John F. Kennedy was assassinated on Elm Street while his motorcade passed through Dealey Plaza in Downtown Dallas.[43] The upper two floors of the building from which the Warren Commission reported assassin Lee Harvey Oswald shot Kennedy have been converted into a historical museum covering the former president's life and accomplishments.[44] Kennedy was pronounced dead at Dallas Parkland Memorial Hospital just over 30 minutes after the shooting.

On July 7, 2016, multiple shots were fired at a Black Lives Matter protest in Downtown Dallas, held against the police killings of two black men from other states. The gunman, later identified as Micah Xavier Johnson, began firing at police officers at 8:58 p.m., killing five officers and injuring nine. Two bystanders were also injured. This marked the deadliest day for U.S. law enforcement since the September 11 attacks. Johnson told police during a standoff that he was upset about recent police shootings of black men and wanted to kill whites, especially white officers.[45][46] After hours of negotiation failed, police resorted to a robot-delivered bomb, killing Johnson inside Dallas College El Centro Campus. The shooting occurred in an area of hotels, restaurants, businesses, and residential apartments only a few blocks away from Dealey Plaza.

Dallas is situated in the Southern United States, in North Texas. It is the county seat of Dallas County and portions of the city extend into neighboring Collin, Denton, Kaufman, and Rockwall counties. Many suburbs surround Dallas; three enclaves are within the city boundaries—Cockrell Hill, Highland Park, and University Park. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 385.8 square miles (999.3 km2); 340.5 square miles (881.9 km2) of Dallas is land and 45.3 square miles (117.4 km2) of it (11.75%) is water.[47] Dallas makes up one-fifth of the much larger urbanized area known as the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, in which one quarter of all Texans live.

Dallas's skyline has twenty buildings classified as skyscrapers, over 490 feet (150 m) in height.[48] Despite its tallest building not reaching 980 feet (300 m), Dallas does have a signature building in Bank of America Plaza which is lit up in neon but falls outside the top two hundred tallest buildings in the world. Although some of Dallas's architecture dates from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, most of the notable architecture in the city is from the modernist and postmodernist eras. Iconic examples of modernist architecture include Reunion Tower, the John Fitzgerald Kennedy Memorial, I. M. Pei's Dallas City Hall and the Morton H. Meyerson Symphony Center.[49] Good examples of postmodernist skyscrapers are Fountain Place, Bank of America Plaza, Renaissance Tower, JPMorgan Chase Tower, and Comerica Bank Tower. Downtown Dallas also has residential offerings in downtown, some of which are signature skyline buildings.

Several smaller structures are fashioned in the Gothic Revival style, such as the Kirby Building, and the neoclassical style, as seen in the Davis and Wilson Buildings. One architectural "hotbed" in the city is a stretch of historic houses along Swiss Avenue, which has all shades and variants of architecture from Victorian to neoclassical.[50] The Dallas Downtown Historic District protects a cross-section of Dallas commercial architecture from the 1880s to the 1940s.

The city of Dallas is home to many areas, neighborhoods, and communities. Dallas can be divided into several geographical areas which include larger geographical sections of territory including many subdivisions or neighborhoods, forming macroneighborhoods.

Central Dallas is anchored by Downtown Dallas, the center of the city, along with Oak Lawn and Uptown, areas characterized by dense retail, restaurants, and nightlife.[51] Downtown Dallas has a variety of named districts, including the West End Historic District, the Arts District, the Main Street District, Farmers Market District, the City Center Business District, the Convention Center District, and the Reunion District. This area includes Uptown, Victory Park, Harwood, Oak Lawn, Dallas Design District, Trinity Groves, Turtle Creek, Cityplace, Knox/Henderson, Greenville, and West Village.

East Dallas is the location of Deep Ellum, an arts area close to Downtown, the Lakewood neighborhood (and adjacent areas, including Lakewood Heights, Wilshire Heights, Lower Greenville, Junius Heights, and Hollywood Heights/Santa Monica), Vickery Place and Bryan Place, and the architecturally significant neighborhoods of Swiss Avenue and Munger Place. Its historic district has one of the largest collections of Frank Lloyd Wright-inspired prairie-style homes in the United States. In the northeast quadrant of the city is Lake Highlands, one of Dallas's most unified middle-class neighborhoods.[52]

Southwest of Downtown lies Oak Cliff. Once a separate city founded in the mid-1800s, Oak Cliff was annexed in 1903 by Dallas.[53] As one of the oldest areas in Dallas, the hilly North Oak Cliff is home to 5 of the 13 conservation districts in Dallas including the architecturally significant Kessler Park neighborhood and trendy Bishop Arts District.

South Dallas is the location of Cedars, and Fair Park, where the annual State Fair of Texas is held from late September through mid-October. Also located here is Exposition Park, Dallas, noted for having artists, art galleries, and bars along tree-lined Exposition Avenue.[54]

South Side Dallas is a popular location for nightly entertainment. The neighborhood has undergone extensive development and community integration. What was once an area characterized by high rates of poverty and crime is now one of the city's most attractive social and living destinations.[55][56]

Further east, in the southeast quadrant of the city, is the large neighborhood of Pleasant Grove. Once an independent city, it is a collection of mostly lower-income residential areas stretching to Seagoville in the southeast. Though a city neighborhood, Pleasant Grove is surrounded by undeveloped land on all sides. Swampland and wetlands separating it from South Dallas are part of the Great Trinity Forest,[57] a subsection of the city's Trinity River Project, newly appreciated for habitat and flood control.

Dallas and its surrounding area are mostly flat. The city lies at elevations ranging from 450 to 550 feet (137 to 168 m) above sea level. The western edge of the Austin Chalk Formation, a limestone escarpment (also known as the "White Rock Escarpment"), rises 230 feet (70 m) and runs roughly north–south through Dallas County. South of the Trinity River, the uplift is particularly noticeable in the neighborhoods of Oak Cliff and the adjacent cities of Cockrell Hill, Cedar Hill, Grand Prairie, and Irving. Marked variations in terrain are also found in cities immediately to the west in Tarrant County surrounding Fort Worth, as well as along Turtle Creek north of Downtown.

Dallas, like many other cities, was founded along a river. The city was founded at the location of a "white rock crossing" of the Trinity River, where it was easier for wagons to cross the river in the days before ferries or bridges. The Trinity River, though not usefully navigable, is the major waterway through the city. Interstate 35E parallels its path through Dallas along the Stemmons Corridor, then south alongside the western portion of Downtown and past South Dallas and Pleasant Grove, where the river is paralleled by Interstate 45 until it exits the city and heads southeast towards Houston. The river is flanked on both sides by 50 feet (15 m) tall earthen levees to protect the city from frequent floods.[58]

Since it was rerouted in the late 1920s, the river has been little more than a drainage ditch within a floodplain for several miles above and below Downtown, with a more normal course further upstream and downstream, but as Dallas began shifting towards postindustrial society, public outcry about the lack of aesthetic and recreational use of the river ultimately gave way to the Trinity River Project,[59] which was begun in the early 2000s.

The project area reaches for over 20 miles (32 km) in length within the city, while the overall geographical land area addressed by the Land Use Plan is approximately 44,000 acres (180 km2) in size—about 20% of the land area in Dallas. Green space along the river encompasses approximately 10,000 acres (40 km2), making it one of the largest and diverse urban parks in the world.[60]

White Rock Lake and Joe Pool Lake are reservoirs that comprise Dallas's other significant water features. Built at the beginning of the 20th century, White Rock Lake Park is a popular destination for boaters, rowers, joggers, and bikers, as well as visitors seeking peaceful respite from the city at the 66-acre (267,000 m2) Dallas Arboretum and Botanical Garden, on the lake's eastern shore. White Rock Creek feeds into White Rock Lake and then exits into the Trinity River southeast of Downtown Dallas. Trails along White Rock Creek are part of the extensive Dallas County Trails System.

Bachman Lake, just northwest of Love Field Airport, is a smaller lake also popularly used for recreation. Northeast of the city is Lake Ray Hubbard, a vast 22,745-acre (92 km2) reservoir in an extension of Dallas surrounded by the suburbs of Garland, Rowlett, Rockwall, and Sunnyvale.[61] To the west of the city is Mountain Creek Lake, once home to the Naval Air Station Dallas (Hensley Field) and a number of defense aircraft manufacturers.[62][63] North Lake, a small body of water in an extension of the city limits surrounded by Irving and Coppell, initially served as a water source for a nearby power plant but is now being targeted for redevelopment as a recreational lake due to its proximity to Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport, a plan the lake's neighboring cities oppose.[64]

| Dallas, Texas | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dallas has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification: Cfa, Trewartha: Cfhk) characteristic of the Southern Plains of the United States. It also has both continental and tropical characteristics, characterized by a relatively wide annual temperature range for the latitude. Located at the lower end of Tornado Alley, it is prone to extreme weather, tornadoes, and hailstorms.

Summers in Dallas are very hot with high humidity, although extended periods of dry weather often occur. July and August are typically the hottest months, with an average high of 96.0 °F (36 °C) and an average low of 76.7 °F (25 °C). Heat indices regularly surpass 105 °F (41 °C) due to elevated humidity during the summer months, making the summer heat almost unbearable. The all-time record high is 113 °F (45 °C), set on June 26 and 27, 1980 during the Heat Wave of 1980 at nearby Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport.[66][67]

Winters in Dallas are usually mild, with occasional cold spells. The average date of first frost is November 12, and the average date of last frost is March 12.[68] January is typically the coldest month, with an average daytime high of 56.8 °F (14 °C) and an average nighttime low of 37.3 °F (3 °C). The normal daily average temperature in January is 47.0 °F (8 °C) but sharp swings in temperature can occur, as strong cold fronts known as "Blue Northers" pass through the Dallas region, forcing temperatures below the 40 °F (4 °C) mark for several days at a time and often between days with high temperatures above 80 °F (27 °C). Snow accumulation is seen in the city in about 70% of winter seasons, and snowfall generally occurs 1–2 days out of the year for a seasonal average of 1.5 inches (4 cm). Some areas in the region, however, receive more than that, while other areas receive negligible snowfall or none at all.[69] The all-time record low temperature within the city is −10 °F (−23 °C), set on February 12, 1899 during the Great Blizzard of 1899.[70] The temperature at nearby Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport reached −2 °F (−19 °C) on February 16, 2021, during the February 2021 North American winter storm.

Spring and autumn are transitional seasons with moderate and pleasant weather. Vibrant wildflowers (such as the bluebonnet, Indian paintbrush and other flora) bloom in spring and are planted around the highways throughout Texas.[71] Springtime weather can be quite volatile, but temperatures themselves are mild. Late spring to early summer also tends to be the most humid, with humidity levels frequently exceeding 75%. The weather in Dallas is also generally pleasant from late September to early December and on many winter days. Autumn often brings more storms and tornado threats, but they are usually fewer and less severe than in spring.

Each spring, cold fronts moving south from the North collide with warm, humid air streaming in from the Gulf Coast, leading to severe thunderstorms with lightning, torrents of rain, hail, and occasionally, tornadoes. Over time, tornadoes have probably been the most significant natural threat to the city, as it is near the heart of Tornado Alley.

A few times each winter in Dallas, warm and humid air from the south will override cold, dry air, resulting in freezing rain or ice and causing disruptions in the city if the roads and highways become slick. Temperatures reaching 70 °F (21 °C) on average occur on at least four days each winter month. Dallas averages 26 annual nights at or below freezing,[66] with the winter of 1999–2000 holding the record for the fewest freezing nights with 14. During this same span of 15 years,[specify] the temperature in the region has only twice dropped below 15 °F (−9 °C), though it will generally fall below 20 °F (−7 °C) in most (67%) years.[66]

The U.S. Department of Agriculture places Dallas in Plant Hardiness Zone 8b.[72][73] However, mild winter temperatures in the past 15 to 20 years had encouraged the horticulture of more cold-sensitive plants such as Washingtonia filifera and Washingtonia robusta palms, nearly all of which died off during the February 2021 North American winter storm. According to the American Lung Association, Dallas has the 12th highest air pollution among U.S. cities, ranking it behind Los Angeles and Houston.[74] Much of the air pollution in Dallas and the surrounding area comes from a hazardous materials incineration plant in the small town of Midlothian and from cement plants in neighboring Ellis County.[75]

The average daily low in Dallas is 57.4 °F (14 °C), and the average daily high is 76.9 °F (25 °C). Dallas receives approximately 39.1 inches (993 mm) of rain per year. The record snowfall for Dallas was 11.2 inches (28 cm) on February 11, 2010.

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °F (°C) | 88 (31) |

95 (35) |

97 (36) |

100 (38) |

103 (39) |

112 (44) |

112 (44) |

111 (44) |

110 (43) |

100 (38) |

92 (33) |

89 (32) |

112 (44) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 76.7 (24.8) |

80.5 (26.9) |

85.9 (29.9) |

89.0 (31.7) |

95.0 (35.0) |

98.9 (37.2) |

103.6 (39.8) |

104.1 (40.1) |

99.1 (37.3) |

92.5 (33.6) |

82.9 (28.3) |

77.9 (25.5) |

105.5 (40.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 57.7 (14.3) |

62.0 (16.7) |

69.9 (21.1) |

77.4 (25.2) |

84.9 (29.4) |

92.7 (33.7) |

96.9 (36.1) |

97.1 (36.2) |

90.0 (32.2) |

79.5 (26.4) |

67.8 (19.9) |

59.2 (15.1) |

77.9 (25.5) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 47.8 (8.8) |

52.0 (11.1) |

59.6 (15.3) |

67.1 (19.5) |

75.4 (24.1) |

83.3 (28.5) |

87.3 (30.7) |

87.3 (30.7) |

80.1 (26.7) |

69.1 (20.6) |

57.8 (14.3) |

49.5 (9.7) |

68.0 (20.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 37.9 (3.3) |

41.9 (5.5) |

49.4 (9.7) |

56.8 (13.8) |

66.0 (18.9) |

73.8 (23.2) |

77.7 (25.4) |

77.4 (25.2) |

70.1 (21.2) |

58.7 (14.8) |

47.8 (8.8) |

39.8 (4.3) |

58.1 (14.5) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 22.5 (−5.3) |

26.5 (−3.1) |

31.1 (−0.5) |

41.3 (5.2) |

52.0 (11.1) |

64.2 (17.9) |

70.8 (21.6) |

69.4 (20.8) |

56.8 (13.8) |

42.0 (5.6) |

31.2 (−0.4) |

25.1 (−3.8) |

19.1 (−7.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −3 (−19) |

2 (−17) |

11 (−12) |

30 (−1) |

39 (4) |

53 (12) |

56 (13) |

57 (14) |

36 (2) |

26 (−3) |

17 (−8) |

1 (−17) |

−3 (−19) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.59 (66) |

2.78 (71) |

3.45 (88) |

3.15 (80) |

4.57 (116) |

3.83 (97) |

2.54 (65) |

2.31 (59) |

3.10 (79) |

4.79 (122) |

2.93 (74) |

3.23 (82) |

39.33 (999) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.1 (0.25) |

0.9 (2.3) |

0.3 (0.76) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.3 (0.76) |

1.7 (4.3) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 7.0 | 6.9 | 8.1 | 7.3 | 9.4 | 7.3 | 4.9 | 5.1 | 5.6 | 7.2 | 6.5 | 6.9 | 82.2 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 1.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 67.5 | 66.4 | 63.7 | 65.3 | 69.7 | 65.8 | 60.0 | 60.5 | 66.5 | 65.7 | 67.4 | 67.5 | 65.4 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 31.3 (−0.4) |

35.2 (1.8) |

42.6 (5.9) |

52.0 (11.1) |

61.0 (16.1) |

66.6 (19.2) |

67.6 (19.8) |

66.7 (19.3) |

63.3 (17.4) |

53.2 (11.8) |

43.7 (6.5) |

34.7 (1.5) |

51.5 (10.8) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 183.5 | 178.3 | 227.7 | 236.0 | 258.4 | 297.8 | 332.4 | 304.5 | 246.2 | 228.1 | 183.8 | 173.0 | 2,849.7 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 58 | 58 | 61 | 61 | 60 | 69 | 76 | 74 | 66 | 65 | 59 | 56 | 64 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| Source 1: NOAA (sun, relative humidity, and dew point 1961–1990 at DFW Airport)[e][77][65][78][79] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas (Average UV index)[80] | |||||||||||||

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 1,073 | — | |

| 1860 | 698 | −34.9% | |

| 1870 | 3,000 | 329.8% | |

| 1880 | 10,358 | 245.3% | |

| 1890 | 38,069 | 267.5% | |

| 1900 | 42,639 | 12.0% | |

| 1910 | 92,104 | 116.0% | |

| 1920 | 158,976 | 72.6% | |

| 1930 | 269,475 | 69.5% | |

| 1940 | 294,734 | 9.4% | |

| 1950 | 434,462 | 47.4% | |

| 1960 | 679,684 | 56.4% | |

| 1970 | 844,401 | 24.2% | |

| 1980 | 904,078 | 7.1% | |

| 1990 | 1,006,977 | 11.4% | |

| 2000 | 1,188,580 | 18.0% | |

| 2010 | 1,197,816 | 0.8% | |

| 2020 | 1,304,379 | 8.9% | |

| 2024 (est.) | 1,304,238 | 0.0% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[81] 2010–2020[3] |

|||

Dallas is the ninth-most-populous city in the United States and third in Texas after the cities of Houston and San Antonio.[12] Its metropolitan area encompasses one-quarter of the population of Texas, and is the largest in the Southern U.S. and Texas followed by the Greater Houston metropolitan area. At the 2020 United States census the city of Dallas had 1,304,379 residents, an increase of 106,563 since the 2010 United States census.[82] However, as of July 1, 2022, the U.S. Census Bureau estimates that Dallas in first years since the 2020 census lost 4,835 people, leaving the city with a population of 1,299,544.[3]

There were 524,498 households at the 2020 estimates,[83] up from 2010's 458,057 households, out of which 137,523 had children under the age of 18 living with them.[84] Approximately 36.2% of households were headed by married couples living together, 57.2% had a single householder male or female with no spouse present, and 35.6% were classified as non-family households with the householder living alone.[83] In 2010, 33.7% of all households had one or more people under 18 years of age, and 17.6% had one or more people who were 65 years of age or older. The average household size in 2020 was 2.52 and the average family size was 3.41.[84] In 2018, the owner-occupied housing rate was 40.2% and the renter-occupied housing rate was 59.8%.[85] At the 2010 census, the city's age distribution of the population showed 26.5% under the age of 18 and 8.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 31.8 years. In 2010, 50.0% of the population was male and 50.0% was female.[86] In 2020, the median age 32.9 years; for every 100 females, there were 98.4 males.[87]

According to the 2020 American Community Survey, the median income for a household in the city was $54,747; families had a median household income of $60,895; married-couple families $81,761; and non-families $45,658.[88] In 2003–2007's survey, male full-time workers had a median income of $32,265 versus $32,402 for female full-time workers. The per capita income for the city was $25,904. About 18.7% of families and 21.7% of the population were below the poverty line, including 33.6% of those under age 18 and 13.4% of those aged 65 or over. Per 2007's survey, the median price for a house was $129,600;[89] by 2020, the median price for a house was valued at $252,300, with 54.4% of owner-occupied units from $50,000 to $299,999.[90]

The 2022 Point-In-Time Homeless Count found there were 4,410 homeless people in Dallas.[91][92] According to the Metro Dallas Homeless Alliance Continuum of Care 2022 Homeless Count & Survey Independent Analysis, "approximately 1 of 3 (31%) those experiencing homelessness were found on the streets or in other places not meant for human habitation."[92]

The region surrounding Dallas is a habitat for mosquitoes, creating a pest problem for humans. Dallas and the surrounding area is sprayed regularly to control mosquito-borne diseases such as West Nile virus.[93]

| Racial composition | 2020[94] | 2010[95] | 1990[96] | 1970[96] | 1950[96] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 42.3% | 42.4% | 20.9% | 7.5%[f] | n/a |

| White (non-Hispanic) | 28.1% | 28.8% | 47.7% | 66.9%[f] | n/a |

| Black or African American | 22.9% | 24.7% | 29.5% | 24.9% | 13.1% |

| Asian | 3.7% | 2.9% | 2.2% | 0.2% | – |

⬤ Black

⬤ Asian

⬤ Hispanic

⬤ Other

Dallas's population was historically predominantly White (non-Hispanic Whites made up 82.8% of the population in 1930),[97] but its population has diversified due to immigration and white flight over the 20th century. Since then, the non-Hispanic White population has declined to less than one-third of the city's population.[98] According to the 2010 U.S. census, 50.7% of the population was White (28.8% non-Hispanic White), 24.8% was Black or African American, 0.7% American Indian and Alaska Native, 2.9% Asian, and 2.6% from two or more races; 42.4% of the total population was of Hispanic or Latino American origin (they may be of any race).[99]

At the U.S. Census Bureau's 2019 estimates, 29.1% were non-Hispanic White 24.3% Black and African American, 0.3% American Indian or Alaska Native, 3.7% Asian, and 1.4% from two or more races.[100] Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islanders made up a total of 312 residents according to 2019's census estimates, down from 606 in 2017.[101] Hispanic or Latino Americans of any race made up 41.2% of the estimated population in 2019. Among the Hispanic or Latino American population in 2019, 34.6% of Dallas was Mexican, 0.4% Puerto Rican, 0.2% Cuban and 6.0% other Hispanic or Latino American. In 2017's American Community Survey estimates among the demographic 35.5% were Mexican, 0.6% Puerto Rican, 0.4% Cuban, and 5.4% other Hispanic or Latino.[102] By 2020, Hispanic or Latino Americans of any race continued to constitute the largest ethnic group in the city proper,[94] reflecting nationwide demographic trends.[103][104][105]

The Dallas area is a major living destination for Mexican Americans and other Hispanic and Latino American immigrants. The southwestern portion of the city, particularly Oak Cliff is chiefly inhabited by Hispanic and Latino American residents.[106][107] The southeastern portion of the city Pleasant Grove is chiefly inhabited by African American and Hispanic or Latino American residents, while the southern portion of the city is predominantly black.[108][109] The west and east sides of the city are predominantly Hispanic or Latino American; Garland also has a large Spanish-speaking population. North Dallas has many enclaves of predominantly white, black and especially Hispanic or Latino American residents.

The Dallas area is also a major living destination for Black and African Americans primarily due to its strong and diverse economy.[110][111] Between 2010 and 2020, the Dallas area had the second-most new Black and African American residents only behind the Atlanta area and slightly above the Houston area.[112] The notable influx of African Americans is partly due to the New Great Migration.[113] There is a significant number of people from the Horn of Africa, immigrants from Ethiopia, Eritrea and Somalia.[114]

The Dallas–Fort-Worth metroplex had an estimated 70,000 Russian-speakers (as of November 6, 2012) mostly immigrants from the former Soviet Bloc.[115] Included in this population are Russians, Russian Jews, Ukrainians, Belarusians, Moldavians, Uzbek, Kirghiz, and others. The Russian-speaking population of Dallas has continued to grow in the sector of "American husbands-Russian wives". Russian DFW has its own newspaper, The Dallas Telegraph.[116][117]

In addition, Dallas and its suburbs are home to a large number of Asian Americans including those of Indian, Vietnamese, Chinese, Korean, Filipino, Japanese, and other heritage.[118][119] Among large-sized cities in the United States, Plano, the northern suburb of Dallas, has the 6th largest Chinese American population as of 2016. The Plano-Richardson area in particular had an estimated 30,000 Iranian Americans in 2012.[120][121] With so many immigrant groups, there are often multilingual signs in the linguistic landscape. According to U.S. Census Bureau data released in December 2013, 23 percent of Dallas County residents were foreign-born, while 16 percent of Tarrant County residents were foreign-born.[122] The 2018 census estimates determined that the city of Dallas's foreign-born population consisted of 25.4% naturalized citizens and 74.6% non-citizens.[123]

Recognized for having one of the largest lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) populations in the nation, Dallas and the Metroplex are widely noted for being home to a vibrant and diverse LGBT community.[124][125] Throughout the year there are many well-established but quite small compared to other cities LGBT events held in the area, most notably the annual Alan Ross Texas Freedom (Pride) Parade and Festival in June which draws approximately 50,000.[126][127] For decades, the Oak Lawn and Bishop Arts districts have been known as the epicenters of LGBT culture in Dallas.[128]

Christianity is the most prevalently practiced religion in Dallas and the wider metropolitan area according to a 2014 study by the Pew Research Center (78%),[130][131] and the Public Religion Research Institute's 2020 study (77%).[132] There is a large Protestant Christian influence in the Dallas community, though the city of Dallas and Dallas County have more Catholic than Protestant residents, while the reverse is usually true for the suburban areas of Dallas and the city of Fort Worth.

Dallas has been called the "Prison Ministry Capital of the World" by the prison ministry community.[133] It is a home for the International Network of Prison Ministries, the Coalition of Prison Evangelists, Bill Glass Champions for Life, Chaplain Ray's International Prison Ministry, and 60 other prison ministries.[134]

Methodist, Baptist, and Presbyterian churches are prominent in many neighborhoods and anchor two of the city's major private universities (Southern Methodist University and Dallas Baptist University). Dallas is also home to two evangelical seminaries: the Dallas Theological Seminary and Criswell College. Many Bible schools including Christ For The Nations Institute are also headquartered in the city. The Christian creationist apologetics group Institute for Creation Research is headquartered in Dallas. According to the Pew Research Center, evangelical Protestantism constituted the largest form of Protestantism in the area as of 2014.[135] The largest single evangelical Protestant group were Baptists. The largest Baptist denomination was the Southern Baptist Convention, followed by the historically black National Baptist Convention USA.[135] African-initiated Protestant churches including Ethiopian Evangelical churches can be found throughout the metropolitan area.[136][137]

The Catholic Church is also a significant religious organization in the Dallas area and operates the University of Dallas, a liberal-arts university in the Dallas suburb of Irving. The Cathedral Santuario de la Virgen de Guadalupe in the Arts District is home to the second-largest Catholic church membership in the United States and overseas,[138] consisting over 70 parishes in the Dallas Diocese. The Society of Jesus operates the Jesuit College Preparatory School of Dallas. Dallas is also home to numerous Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox churches including Saint Seraphim Cathedral, see of the Orthodox Church in America's Southern Diocese.[139] The Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America (Ecumenical Patriarchate) has one parish in the city of Dallas.[140]

Jehovah's Witnesses has a large number of members throughout the Dallas metropolitan division. In addition, there are several Unitarian Universalist congregations, including First Unitarian Church of Dallas, founded in 1899.[141] A large community of the United Church of Christ exists in the city. The most prominent UCC-affiliated church is the Cathedral of Hope, a predominantly LGBT-affirming church.[142]

Since the establishment of the city's first Jewish cemetery in 1854 and its first congregation (which would eventually be known as Temple Emanu-El) in 1873, Dallasite Jews have been well represented among leaders in commerce, politics, and various professional fields in Dallas and elsewhere.[143][144] Furthermore, a large Muslim community exists in the north and northeastern portions of Dallas, as well as in the northern Dallas suburbs.[145] The oldest mosque in Dallas is Masjid Al-Islam just south of Downtown.[146][147]

Dallas has a large Buddhist community. Immigrants from East Asia, Southeast Asia, Nepal, and Sri Lanka have all contributed to the Buddhist population, which is concentrated in the northern suburbs of Garland, Plano and Richardson. Numerous Buddhist temples dot the Metroplex including The Buddhist Center of Dallas, Lien Hoa Vietnamese Temple of Irving, and Kadampa Meditation Center Texas and Wat Buddhamahamunee of Arlington. A large and growing Hindu Community lives in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex. Most live in Collin County and the northern portions of Dallas County. Over 28 Hindu Temples exist in the area. Some notable ones include the DFW Hindu Temple, the North Texas Hindu Mandir, Radha Krishna Temple, Dallas and Karya Siddhi Hanuman Temple.[148] There are also at least three Sikh Gurudwaras in this metropolitan area.[149][150][151] For irreligious people, the Winter Solstice Celebration is held in the Metroplex although some of its participants are also neo-pagans and New Agers.[152]

According to the FBI, a city to city comparison of crime rates can be misleading, because recording practices vary from city to city, citizens report different percentages of crimes from one city to the next, and the actual number of people physically present in a city is unknown.[153] With that in mind, Dallas has one of the top 10 crime rates in Texas and its crime rate is higher than the national average.[154][155]

Since 2020, Dallas' murder rate has seen a notable increase. In 2020, Dallas recorded 251 murders which was a 20-year high. By 2022 it decreased to 214 but then increased to 246 in 2023.[156] As of 2020, the gang presence in Dallas has grown significantly and is heavily responsible for the spike in crime.[157] Dallas leaders have made crime reduction a major priority.[158][159]

| Top publicly traded companies in Dallas for 2017 according to revenues with Dallas and U.S. ranks. |

|||||

| DAL | Corporation | US | |||

| 1 | AT&T | 9 | |||

| 2 | Energy Transfer Equity | 79 | |||

| 3 | Tenet Healthcare | 134 | |||

| 4 | Southwest Airlines | 138 | |||

| 5 | Texas Instruments | 206 | |||

| 6 | Jacobs Engineering | 259 | |||

| 7 | HF Sinclair | 274 | |||

| 8 | Dean Foods | 351 | |||

| 9 | Builders FirstSource | 421 | |||

| Source: Dallas Morning News[160] | |||||

In its beginnings, Dallas relied on farming, neighboring Fort Worth's Stockyards, and its prime location on Native American trade routes to sustain itself. Dallas' key to growth came in 1873 with the construction of multiple rail lines through the city. As Dallas grew and technology developed, cotton became its boon and by 1900, Dallas was the largest inland cotton market in the world, becoming a leader in cotton gin machinery manufacturing.

By the early 1900s, Dallas was a hub for economic activity all over the Southern United States and was selected in 1914 as the seat of the Eleventh Federal Reserve District. By 1925, Texas churned out more than 1⁄3 of the nation's cotton crop, with 31% of Texas cotton produced within a 100-mile (160 km) radius of Dallas. In the 1930s, petroleum was discovered east of Dallas, near Kilgore. Dallas' proximity to the discovery put it immediately at the center of the nation's petroleum market. Petroleum discoveries in the Permian Basin, the Panhandle, the Gulf Coast, and Oklahoma in the following years further solidified Dallas' position as the hub of the market.[161]

The end of World War II left Dallas seeded with a nexus of communications, engineering, and production talent by companies such as Collins Radio Corporation. Decades later, the telecommunications and information revolutions still drive a large portion of the local economy. The city is sometimes referred to as the heart of "Silicon Prairie" because of a high concentration of telecommunications companies in the region, the epicenter of which lies along the Telecom Corridor in Richardson, a northern suburb of Dallas. The Telecom Corridor is home to more than 5,700 companies including Texas Instruments (headquartered in Dallas), Nortel Networks, Alcatel Lucent, AT&T, Ericsson, Fujitsu, Nokia, Rockwell Collins, Cisco Systems, T-Mobile, Verizon Communications, and CompUSA (which is now headquartered in Miami, Florida).[162] Texas Instruments, a major manufacturer, employs 10,400 people at its corporate headquarters and chip plants in Dallas.[163]

In the 1980s Dallas was a real estate hotbed, with the increasing metropolitan population bringing with it a demand for new housing and office space. Several of Downtown Dallas' largest buildings are the fruit of this boom, but over-speculation, the savings and loan crisis and an oil bust brought the 1980s building boom to an end for Dallas as well as its sister city Houston. Between the late 1980s and the early 2000s, central Dallas went through a slow period of growth. However, since the early 2000s the central core of Dallas has been enjoying steady and significant growth encompassing both repurposing of older commercial buildings in Downtown Dallas into residential and hotel uses, as well as the construction of new office and residential towers. The opening of Klyde Warren Park, built across Woodall Rodgers Freeway seamlessly connecting the central Dallas CBD to Uptown/Victory Park, has acted synergistically with the highly successful Dallas Arts District, so both have become catalysts for significant new development in central Dallas.

The residential real estate market in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex has not only been resilient but has once again returned to a boom status. Dallas and the greater metro area have been leading the nation in apartment construction and net leasing, with rents reaching all-time highs. Single family home sales, whether pre-owned or new construction, along with home price appreciation, were leading the nation since 2015.[164][165]

A sudden drop in the price of oil, starting in mid-2014 and accelerating throughout 2015, has not significantly affected Dallas and its greater metro area due to the highly diversified nature of its economy. Dallas and the metropolitan region continue to see strong demand for housing, apartment and office leasing, shopping center space, warehouse and industrial space with overall job growth remaining very robust. Oil-dependent cities and regions have felt significant effects from the downturn, but Dallas's growth has continued unabated, strengthening in 2015. Significant national headquarters relocations to the area (as exemplified by Toyota's decision to leave California and establish its new North American headquarters in the Dallas area) coupled with significant expansions of regional offices for a variety of corporations and along with company relocations to Downtown Dallas helped drive the boom in the Dallas economy.

The Dallas–Fort Worth area has one of the largest concentrations of corporate headquarters for publicly traded companies in the United States. Fortune Magazine's 2022 annual list of the Fortune 500 in America indicates the city of Dallas had 11 Fortune 500 companies,.[19] and the DFW region as a whole had 23.[18] As of 2022, Dallas–Fort Worth represents the second-largest concentration of Fortune 500 headquarters in Texas and fourth-largest in the United States, behind the metropolitan areas of Houston (24), Chicago (35) and New York (62).[18]

In 2008, AT&T relocated their headquarters to Downtown Dallas;[166] AT&T is the largest telecommunications company in the world and was the ninth largest company in the nation by revenue for 2017.[167] Additional Fortune 500 companies headquartered in Dallas in order of ranking include Energy Transfer Equity, CBRE (which moved its headquarters from Los Angeles to Dallas in 2020),[168][169] Tenet Healthcare, Southwest Airlines, Texas Instruments, Jacobs Engineering, HollyFrontier, Dean Foods, and Builders FirstSource. In October 2016, Jacobs Engineering, one of the world's largest engineering companies, relocated from Pasadena, California to Downtown Dallas.[170]

Nearby Irving is home to six Fortune 500 companies of its own, including McKesson, the country's largest pharmaceutical distributor and listed at number seven overall on the 2021 Fortune 500 list,[171][172][173] Fluor (engineering), Kimberly-Clark, Celanese, Michaels Companies, and Vistra Energy.[174] Plano is home to an additional four Fortune 500 companies, including J.C. Penney, Alliance Data Systems, Yum China, and Dr. Pepper Snapple.[174] Fort Worth is home to two Fortune 500 companies, including American Airlines, the largest airline in the world by revenue, fleet size, profit, passengers carried and revenue passenger mile and D.R. Horton, the largest homebuilder in America.[174] Westlake, TX, north of Fort Worth, now has two Fortune 500 companies: Financial services giant, Charles Schwab, and convenience store distributor, Core-Mark.[175][176] One Fortune 500 company, GameStop, is based in Grapevine.

Additional major companies headquartered in Dallas and its metro area include Comerica, which relocated its national headquarters to Downtown Dallas from Detroit in 2007,[177] NTT DATA Services, Regency Energy Partners, Atmos Energy, Neiman Marcus, AECOM, Think Finance, 7-Eleven, Brinker International, Primoris Services, AMS Pictures, id Software, Mary Kay Cosmetics, Chuck E. Cheese's, Zale Corporation, and Fossil, Inc. Many of these companies—and others throughout the DFW metroplex—comprise the Dallas Regional Chamber. Susan G. Komen for the Cure, the world's largest breast cancer organization, was founded and is headquartered in Dallas.[178]

In addition to its large number of businesses, Dallas has more shopping centers per capita than any other city in the United States and is also home to the second shopping center ever built in the United States, Highland Park Village, which opened in 1931.[179] Dallas is home of the two other major malls in North Texas, the Dallas Galleria and NorthPark Center, which is the second largest mall in Texas. Both malls feature high-end stores and are major tourist draws for the region.[180][181]

Dallas is the third most popular destination for business travel in the United States, and the Kay Bailey Hutchison Convention Center is one of the largest and busiest convention centers in the country, at over 1,000,000 square feet (93,000 m2), and the world's single-largest column-free exhibit hall.[182] VisitDallas is the 501(c)(6) organization contracted to promote tourism and attract conventions but an audit released in January 2019 cast doubts on its effectiveness in achieving those goals.[183]

The Arts District in the northern section of Downtown is home to several arts venues and is the largest contiguous arts district in the United States.[184] Notable venues in the district include the Dallas Museum of Art; the Morton H. Meyerson Symphony Center, home to the Dallas Symphony Orchestra and Dallas Wind Symphony; the Nasher Sculpture Center; and the Trammell & Margaret Crow Collection of Asian Art.

The Perot Museum of Nature and Science, also in Downtown Dallas, is a natural history and science museum. Designed by 2005 Pritzker Architecture Prize Laureate Thom Mayne and his firm Morphosis Architects, the 180,000-square-foot (17,000 m2) facility has six floors and stands about 14 stories high.

Venues that are part of the AT&T Dallas Center for the Performing Arts include Moody Performance Hall, home to the Dallas Chamber Symphony; the Dee and Charles Wyly Theatre, home to the Dallas Theater Center and the Dallas Black Dance Theatre; and the Winspear Opera House, home to the Dallas Opera and Texas Ballet Theater.[185][186]

Not far north of the area is the Meadows Museum at Southern Methodist University. In 2009, it joined up with Madrid's Prado Museum for a three-year partnership. The Prado focuses on Spanish visual art and has a collection of Spanish art in North America, with works by de Juanes, El Greco, Fortuny, Goya, Murillo, Picasso, Pkensa, Ribera, Rico, Velasquez, Zurbaran, and other Spaniards.

These works, as well as non-Spanish highlights like sculptures by Rodin and Moore, have been so successful of a collaboration that the Prado and Meadows have agreed upon an extension of the partnership.[187]

The Institute for Creation Research operates the ICR Discovery Center for Science & Earth History, a creationism museum, in Dallas.[188] The former Texas School Book Depository, from which, according to the Warren Commission Report, Lee Harvey Oswald shot and killed President John F. Kennedy in 1963, has served since the 1980s as a county government office building, except for its sixth and seventh floors, which house the Sixth Floor Museum.

The American Museum of the Miniature Arts is at the Hall of State in Fair Park. The Arts District is also home to DISD's Booker T. Washington High School for the Performing and Visual Arts, a magnet school that was recently expanded.[189] City Center District, next to the Arts District, is home to the Dallas Contemporary.

Deep Ellum, immediately east of Downtown, originally became popular during the 1920s and 1930s as the prime jazz and blues hot spot in the South.[190] Artists such as Blind Lemon Jefferson, Robert Johnson, Huddie "Lead Belly" Ledbetter, and Bessie Smith played in original Deep Ellum clubs such as the Harlem and the Palace. Today, Deep Ellum is home to hundreds of artists who live in lofts and operate in studios throughout the district alongside bars, pubs, and concert venues.[191]

A major art infusion in the area results from the city's lax stance on graffiti, and a number of public spaces, including tunnels, sides of buildings, sidewalks, and streets, are covered in murals. One major example, the Good-Latimer tunnel, was torn down in late 2006 to accommodate the construction of a light rail line through the site.[192]

Like Deep Ellum before it, the Cedars neighborhood to the south of Downtown has also seen a growing population of studio artists and an expanding roster of entertainment venues. The area's art scene began to grow in the early 2000s with the opening of Southside on Lamar, an old Sears Roebuck and Company warehouse converted into lofts, studios, and retail.[193]

Current attractions include Gilley's Dallas and Poor David's Pub.[194][195] Dallas Mavericks owner and local entrepreneur Mark Cuban purchased land along Lamar Street near Cedars Station in September 2005, and locals speculate he is planning an entertainment complex for the site.[196]

South of the Trinity River, the Bishop Arts District in Oak Cliff is home to a number of studio artists living in converted warehouses. Walls of buildings along alleyways and streets are painted with murals, and the surrounding streets contain many eclectic restaurants and shops.[197]

Dallas has an Office of Cultural Affairs as a department of the city government. The office is responsible for six cultural centers throughout the city, funding for local artists and theaters, initiating public art projects, and running the city-owned classical radio station WRR.[198] The Los Angeles-class submarine USS Dallas was planned to become a museum ship near the Trinity River after her decommissioning in September 2014, but this has since been delayed.[199] It will be taken apart into massive sections in Houston and be transported by trucks to the museum site and will be put back together.

The city is served by the Dallas Public Library system. The system was created by the Dallas Federation of Women's Clubs with efforts spearheaded by then president May Dickson Exall. Her fundraising efforts led to a grant from philanthropist and steel baron Andrew Carnegie, which allowed the library system to build its first branch in 1901.[200]

Today, the library operates 30 branch locations throughout the city, including the 8-story J. Erik Jonsson Central Library in the Government District of Downtown.[201]

Dallas is known for its barbecue, authentic Mexican, and Tex-Mex cuisine. Famous products of the Dallas culinary scene include the Frozen margarita machine by restaurateur Mariano Martinez in 1971.[202]

The State Fair of Texas has been held annually at Fair Park since 1886, and generates an estimated $50 million to the city's economy annually.[203] The Red River Shootout,[204] a football game that pits the University of Texas at Austin against the University of Oklahoma at the Cotton Bowl, also brings significant crowds to the city. The city also hosts the State Fair Classic and Heart of Dallas Bowl at the Cotton Bowl.

Other festivals include several Cinco de Mayo celebrations hosted by the city's large Mexican American population and a Saint Patrick's Day parade along Lower Greenville Avenue, Juneteenth festivities, Taste of Dallas, the Deep Ellum Arts Festival, the Greek Food Festival of Dallas, the annual Halloween event "The Wake", and two annual events on Halloween, including a Halloween parade on Cedar Springs Road and a "Zombie Walk" held in Downtown Dallas in the Arts District.

With the opening of Victory Park, WFAA began hosting an annual New Year's Eve celebration in AT&T Plaza that the television station hoped would be reminiscent of celebrations in New York's Times Square; New Year's Eve 2011 set a new record of 32,000 people in attendance.[205]

After the discontinuance of the "Big D NYE" festivities a few years later, a new end-of-year event was started downtown, with a big fireworks show put on at Reunion Tower, which has since aired on KXAS and other TV stations around the state and region. Also, several Omni hotels in the Dallas area host large events to welcome in the new year, including murder mystery parties, rave-inspired events, and other events.

Downtown Dallas is home to two major league sports teams that play at the American Airlines Center: the Dallas Mavericks (NBA), who won the NBA Championship in 2011, and the Dallas Stars (NHL), who won the Stanley Cup in 1999. Nearby Arlington is home to the Dallas Cowboys (NFL), who play at the AT&T Stadium and have won five Super Bowls, the Texas Rangers (MLB), who play at Globe Life Field[206][207] and won the World Series in 2023, and the Dallas Wings (WNBA), who play at College Park Center. MLS team FC Dallas plays at Toyota Stadium in Frisco and won the Lamar Hunt U.S. Open Cup in 1997 and 2016. Additionally, there are several minor league and college sports programs in the area.

Since joining the league as an expansion team in 1960, the Cowboys have enjoyed substantial success, advancing to eight Super Bowls and winning five. The Cowboys are financially the most valuable sports franchise in the world, worth approximately $4 billion.[208] In 2009, they relocated to their new 80,000-seat stadium in Arlington, which was the site of Super Bowl XLV[209] and is set to host the most matches during the 2026 FIFA World Cup.[210][211] The Cowboys are currently part of the East Division of the National Football Conference (NFC).

The Texas Rangers won the American League pennant in 2010, 2011 and 2023, and won the World Series in 2023. The franchise relocated from Washington D.C. in 1972. They play in the West Division of the American League.

The Dallas Mavericks joined the league as an expansion team in 1980. They won their first National Basketball Association championship in 2011 led by Dirk Nowitzki.[212] They play in the Southwest Division of the Western Conference.

The Dallas Stars moved to North Texas in 1993 as a relocation from the former team, the Minnesota North Stars. The Stars have won eight division titles in Dallas, two Presidents' Trophies as the top regular season team in the NHL, the Western Conference championship three times, and in 1998–99, the Stanley Cup. The team plays in the Central Division of the Western Conference.

FC Dallas play at Toyota Stadium (formerly FC Dallas Stadium and Pizza Hut Park), a stadium that opened in 2005.[213] They currently play in MLS's Western Conference. The team was originally called the Dallas Burn and used to play in the Cotton Bowl. Although FC Dallas has not yet won a MLS Cup, they won the Lamar Hunt U.S. Open Cup in 1997 and 2016 and the Supporters' Shield in 2016. Previously, the Dallas Tornado played in the North American Soccer League from 1968 to 1981.

The Dallas Wings came to The Metroplex in 2016 after relocating from Tulsa.

There are many notable minor league teams in the Dallas-Fort Worth. The Allen Americans are a professional ice hockey team headquartered at the Credit Union of Texas Event Center in Allen, Texas, which currently plays in the ECHL. They are the minor league affiliate of the NHL's Seattle Kraken. The team was founded in 2009 in the Central Hockey League(CHL). They have won 4 straight championships, 2 in the CHL (2012–13, 2013–14) and 2 in the ECHL(2014–15, 2015–16).

The Dallas Renegades are a professional football team in the relaunched XFL that plays their home games at Globe Life Park, the former home of the Texas Rangers.[214]

The Dallas Sidekicks (2012) are an American professional indoor soccer team based in Allen, Texas, a suburb of Dallas. They play their home games in the Credit Union of Texas Event Center. The team is named after the original Dallas Sidekicks that operated from 1984 to 2004. The MLS-affiliated North Texas SC team is a member of MLS Next Pro and plays in Frisco at Toyota Stadium; it is the reserve team of FC Dallas. The Dallas Mavericks own an NBA G League team, the Texas Legends.

Rugby is a developing sport in Dallas and Texas in general. The multiple clubs, ranging from men's and women's clubs to collegiate and high school, are part of the Texas Rugby Football Union.[215] Dallas was one of only 16 cities in the United States included in the Rugby Super League,[216] represented by Dallas Harlequins.[217] In 2020, Major League Rugby announced the Dallas Jackals as a new franchise.[218] Australian rules football is also growing in Dallas. The Dallas Magpies, founded in 1998, compete in the United States Australian Football League.

The only Division I sports program within the Dallas political boundary is the Dallas Baptist University Patriots baseball team.[219][220] Although outside the city limits, the Mustangs of Southern Methodist University are in the enclave of University Park. Neighboring cities Fort Worth, Arlington, and Denton are home to the Texas Christian University Horned Frogs, UT Arlington Mavericks, and University of North Texas Mean Green respectively. The Dallas area hosted the Final Four of the 2014 NCAA Men's Division I Basketball Tournament at AT&T Stadium. The college Cotton Bowl Classic football game was played at the Cotton Bowl through its 2009 game, but has moved to AT&T Stadium.

The Red River Showdown is an American college football rivalry game played annually at the Cotton Bowl Stadium during the second weekend of the State Fair of Texas in October. The game is played by the Oklahoma Sooners football team of the University of Oklahoma and the Texas Longhorns football team of the University of Texas at Austin. The 10,000-capacity Forester Stadium, which is used mainly for football and soccer, is also located in Dallas.[221][222]

Dallas maintains and operates 406 parks on 21,000 acres (85 km2) of parkland.[223][224] The city's parks contain 17 separate lakes, including White Rock and Bachman lakes, spanning a total of 4,400 acres (17.81 km2). In addition, Dallas is traversed by 61.6 miles (99.1 km) of biking and jogging trails, including the Katy Trail, and is home to 47 community and neighborhood recreation centers, 276 sports fields, 60 swimming pools, 232 playgrounds, 173 basketball courts, 112 volleyball courts, 126 play slabs, 258 neighborhood tennis courts, 258 picnic areas, six 18-hole golf courses, two driving ranges, and 477 athletic fields as of 2013.[225]

Dallas's flagship park is Fair Park. Built in 1936 for the Texas Centennial Exposition world's fair, Fair Park is the world's largest collection of Art Deco exhibit buildings, art, and sculptures; Fair Park is also home to the State Fair of Texas, the largest state fair in the United States. In November 2019, consultants presented to the public a master plan to revitalize the area.[226]

Named after Klyde Warren, the young son of billionaire Kelcy Warren, Klyde Warren Park was built above Woodall Rodgers Freeway and connects Uptown and Downtown, specifically the Arts District. Klyde Warren Park is home to an amphitheater, jogging trails, a children's park, a dog park, a putting green, croquet, ping pong, chess, an outdoor library, and two restaurants. Food trucks give another option of dining and are lined along the park's Downtown side. There are also weekly planned events, including yoga, Zumba, skyline tours, tai chi, and meditation.[227] Klyde Warren Park is home to a free trolley stop on Olive St., which riders can connect to Downtown, McKinney Avenue, and West Village.

Built in 1913, Turtle Creek Parkway park is a 23.7-acre (9.6 ha) linear park in between Turtle Creek and Turtle Creek Boulevard in the aptly named Turtle Creek neighborhood.[228] Archaeological surveys discovered dart points and flint chips dating 3,000 years to 1,000 BCE. This site was later discovered to be home to Native Americans who cherished the trees and natural spring water. The park is across Turtle Creek from Kalita Humphreys Theater, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright.

Opened on July 4, 1906, Lake Cliff Park was called "the Southwest's Greatest Playground". The park was home to an amusement park, a large pool, waterslides, the world's largest skating rink, and three theaters, the largest being the 2,500-seat Casino Theater. After the streetcar bridge that brought most of the park visitors collapsed, Lake Cliff Park was sold. The Casino Theater moved and the pool was demolished after a polio scare in 1959. The pool was Dallas's first municipal pool.[229]

In 1935, Dallas purchased 36 acres (15 ha) from John Cole's estate to develop Reverchon Park.[230] Reverchon Park was named after botanist Julien Reverchon, who left France to live in the La Reunion colony, which was founded in the mid-1800s[231] and was situated in present-day West Dallas. Reverchon Park was planned to be the crown jewel of the Dallas park system and was even referred to as the "Central Park" of Dallas. Improvements were made throughout the years, including the Iris Bowl, picnic settings, a baseball diamond, and tennis courts. The Iris Bowl celebrated many Greek pageants, dances, and other performances. The Gill Well was installed for nearby residents and drew people all across Texas who wanted to experience the water's healing powers.[232] The baseball diamond was host to a 1953 exhibition game for the New York Giants and the Cleveland Indians.[233]

As part of the ongoing Trinity River Project, the Great Trinity Forest, at 6,000 acres (24 km2), is the largest urban hardwood forest in the United States and is part of the largest urban park in the United States.[57] The Trinity River Audubon Center is a new addition to the park. Opened in 2008, it serves as a gateway to many trails and other nature-viewing activities in the area. The Trinity River Audubon Center is the first LEED-certified building built by the City of Dallas Parks and Recreation Department.

Named after its former railroad name, the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad (or "MKT" Railroad), the 3.5-mile (5.6 km) stretch of railroad was purchased by the city of Dallas and transformed into the city's premier trail. Stretching from Victory Park, the 30-acre (12 ha) Katy Trail passes through the Turtle Creek and Knox Park neighborhoods and runs along the east side of Highland Park. The trail ends at Central Expressway, but extensions are underway to extend the trail to the White Rock Lake Trail in Lakewood.[229]

Dallas hosts three of the twenty-one preserves of the extensive 3,200 acres (13 km2) Dallas County Preserve System. The Joppa Preserve, the McCommas Bluff Preserve, and the Cedar Ridge Preserve are within the Dallas city limits. The Cedar Ridge Preserve was known as the Dallas Nature Center, but the Audubon Dallas group now manages the 633-acre (2.56 km2) natural habitat park on behalf of the city of Dallas and Dallas County. The preserve sits at an elevation of 755 feet (230 m) above sea level and offers a variety of outdoor activities, including 10 miles (16 km) of hiking trails and picnic areas.

The city is also home to Texas's first and largest zoo, the 106-acre (0.43 km2) Dallas Zoo, which opened at its current location in 1888.[234][235]