Movement of goods or people between locations

For other uses, see Transport (disambiguation).

"Transportation" redirects here. For other uses, see Transportation (disambiguation).

|

|

This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.

Find sources: "Transport" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (March 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this message)

|

Main modes of transportation: air, land, water, and space.

Main modes of transportation: air, land, water, and space.

Transport (in British English) or transportation (in American English) is the intentional movement of humans, animals, and goods from one location to another. Modes of transport include air, land (rail and road), water, cable, pipelines, and space. The field can be divided into infrastructure, vehicles, and operations. Transport enables human trade, which is essential for the development of civilizations.

Transport infrastructure consists of both fixed installations, including roads, railways, airways, waterways, canals, and pipelines, and terminals such as airports, railway stations, bus stations, warehouses, trucking terminals, refueling depots (including fuel docks and fuel stations), and seaports. Terminals may be used both for the interchange of passengers and cargo and for maintenance.

Means of transport are any of the different kinds of transport facilities used to carry people or cargo. They may include vehicles, riding animals, and pack animals. Vehicles may include wagons, automobiles, bicycles, buses, trains, trucks, helicopters, watercraft, spacecraft, and aircraft.

Modes

[edit]

Main article: Mode of transport

Various modes of transport in Manchester, England

Various modes of transport in Manchester, England

A mode of transport is a solution that makes use of a certain type of vehicle, infrastructure, and operation. The transport of a person or of cargo may involve one mode or several of the modes, with the latter case being called inter-modal or multi-modal transport. Each mode has its own advantages and disadvantages, and will be chosen on the basis of cost, capability, and route.

Governments deal with the way the vehicles are operated, and the procedures set for this purpose, including financing, legalities, and policies. In the transport industry, operations and ownership of infrastructure can be either public or private, depending on the country and mode.

Passenger transport may be public, where operators provide scheduled services, or private. Freight transport has become focused on containerization, although bulk transport is used for large volumes of durable items. Transport plays an important part in economic growth and globalization, but most types cause air pollution and use large amounts of land. While it is heavily subsidized by governments, good planning of transport is essential to make traffic flow and restrain urban sprawl.

Human-powered

[edit]

Main article: Human-powered transport

Human-powered transport remains common in developing countries.

Human-powered transport remains common in developing countries.

Human-powered transport, a form of sustainable transport, is the transport of people or goods using human muscle-power, in the form of walking, running, and swimming. Modern technology has allowed machines to enhance human power. Human-powered transport remains popular for reasons of cost-saving, leisure, physical exercise, and environmentalism; it is sometimes the only type available, especially in underdeveloped or inaccessible regions.

Although humans are able to walk without infrastructure, the transport can be enhanced through the use of roads, especially when using the human power with vehicles, such as bicycles and inline skates. Human-powered vehicles have also been developed for difficult environments, such as snow and water, by watercraft rowing and skiing; even the air can be entered with human-powered aircraft.

Animal-powered

[edit]

Main article: Animal-powered transport

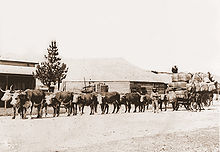

Animal-powered transport is the use of working animals for the movement of people and commodities. Humans may ride some of the animals directly, use them as pack animals for carrying goods, or harness them, alone or in teams, to pull sleds or wheeled vehicles.

Air

[edit]

Main article: Aviation

An Air France Airbus A318 landing at London Heathrow Airport

An Air France Airbus A318 landing at London Heathrow Airport

A fixed-wing aircraft, commonly called an airplane, is a heavier-than-air craft where movement of the air in relation to the wings is used to generate lift. The term is used to distinguish this from rotary-wing aircraft, where the movement of the lift surfaces relative to the air generates lift. A gyroplane is both fixed-wing and rotary wing. Fixed-wing aircraft range from small trainers and recreational aircraft to large airliners and military cargo aircraft.

Two things necessary for aircraft are air flow over the wings for lift and an area for landing. The majority of aircraft also need an airport with the infrastructure for maintenance, restocking, and refueling and for the loading and unloading of crew, cargo, and passengers.[1] While the vast majority of aircraft land and take off on land, some are capable of take-off and landing on ice, snow, and calm water.

The aircraft is the second fastest method of transport, after the rocket. Commercial jets can reach up to 955 kilometres per hour (593 mph), single-engine aircraft 555 kilometres per hour (345 mph). Aviation is able to quickly transport people and limited amounts of cargo over longer distances, but incurs high costs and energy use; for short distances or in inaccessible places, helicopters can be used. As of April 28, 2009, The Guardian article notes that "the WHO estimates that up to 500,000 people are on planes at any time."[3]

Land

[edit]

Main article: Land transport

Land transport covers all land-based transport systems that provide for the movement of people, goods, and services. Land transport plays a vital role in linking communities to each other. Land transport is a key factor in urban planning. It consists of two kinds, rail and road.

Rail

[edit]

Main article: Rail transport

Intercity Express, a German high-speed passenger train

Intercity Express, a German high-speed passenger train

The Beijing Subway is one of the world's largest and busiest rapid transit networks.

The Beijing Subway is one of the world's largest and busiest rapid transit networks.

Rail transport is where a train runs along a set of two parallel steel rails, known as a railway or railroad. The rails are anchored perpendicular to ties (or sleepers) of timber, concrete, or steel, to maintain a consistent distance apart, or gauge. The rails and perpendicular beams are placed on a foundation made of concrete or compressed earth and gravel in a bed of ballast. Alternative methods include monorail and maglev.

A train consists of one or more connected vehicles that operate on the rails. Propulsion is commonly provided by a locomotive, that hauls a series of unpowered cars, that can carry passengers or freight. The locomotive can be powered by steam, by diesel, or by electricity supplied by trackside systems. Alternatively, some or all the cars can be powered, known as a multiple unit. Also, a train can be powered by horses, cables, gravity, pneumatics, and gas turbines. Railed vehicles move with much less friction than rubber tires on paved roads, making trains more energy efficient, though not as efficient as ships.

Intercity trains are long-haul services connecting cities; modern high-speed rail is capable of speeds up to 350 km/h (220 mph), but this requires specially built track. Regional and commuter trains feed cities from suburbs and surrounding areas, while intra-urban transport is performed by high-capacity tramways and rapid transits, often making up the backbone of a city's public transport. Freight trains traditionally used box cars, requiring manual loading and unloading of the cargo. Since the 1960s, container trains have become the dominant solution for general freight, while large quantities of bulk are transported by dedicated trains.

Road

[edit]

Main article: Road transport

Road transport

Road transport

A road is an identifiable route, way, or path between two or more places.[5] Roads are typically smoothed, paved, or otherwise prepared to allow easy travel;[6] though they need not be, and historically many roads were simply recognizable routes without any formal construction or maintenance. In urban areas, roads may pass through a city or village and be named as streets, serving a dual function as urban space easement and route.[8]

The most common road vehicle is the automobile; a wheeled passenger vehicle that carries its own motor. Other users of roads include buses, trucks, motorcycles, bicycles, and pedestrians. As of 2010, there were 1.015 billion automobiles worldwide. Road transport offers complete freedom to road users to transfer the vehicle from one lane to the other and from one road to another according to the need and convenience. This flexibility of changes in location, direction, speed, and timings of travel is not available to other modes of transport. It is possible to provide door-to-door service only by road transport.

Automobiles provide high flexibility with low capacity, but require high energy and area use, and are the main source of harmful noise and air pollution in cities;[9] buses allow for more efficient travel at the cost of reduced flexibility. Road transport by truck is often the initial and final stage of freight transport.

Water

[edit]

Main article: Maritime transport

Automobile ferry in Croatia

Automobile ferry in Croatia

Water transport is movement by means of a watercraft—such as a barge, boat, ship, or sailboat—over a body of water, such as a sea, ocean, lake, canal, or river. The need for buoyancy is common to watercraft, making the hull a dominant aspect of its construction, maintenance, and appearance.

In the 19th century, the first steam ships were developed, using a steam engine to drive a paddle wheel or propeller to move the ship. The steam was produced in a boiler using wood or coal and fed through a steam external combustion engine. Now most ships have an internal combustion engine using a slightly refined type of petroleum called bunker fuel. Some ships, such as submarines, use nuclear power to produce the steam. Recreational or educational craft still use wind power, while some smaller craft use internal combustion engines to drive one or more propellers or, in the case of jet boats, an inboard water jet. In shallow draft areas, hovercraft are propelled by large pusher-prop fans. (See Marine propulsion.)

Although it is slow compared to other transport, modern sea transport is a highly efficient method of transporting large quantities of goods. Commercial vessels, nearly 35,000 in number, carried 7.4 billion tons of cargo in 2007.[10] Transport by water is significantly less costly than air transport for transcontinental shipping; short sea shipping and ferries remain viable in coastal areas.

Other modes

[edit]

Trans-Alaska Pipeline for crude oil

Trans-Alaska Pipeline for crude oil

Pipeline transport sends goods through a pipe; most commonly liquid and gases are sent, but pneumatic tubes can also send solid capsules using compressed air. For liquids/gases, any chemically stable liquid or gas can be sent through a pipeline. Short-distance systems exist for sewage, slurry, water, and beer, while long-distance networks are used for petroleum and natural gas.

Cable transport is a broad mode where vehicles are pulled by cables instead of an internal power source. It is most commonly used at steep gradient. Typical solutions include aerial tramways, elevators, and ski lifts; some of these are also categorized as conveyor transport.

Spaceflight is transport outside Earth's atmosphere by means of a spacecraft. It is most frequently used for satellites placed in Earth orbit. However, human spaceflight mission have landed on the Moon and are occasionally used to rotate crew-members to space stations. Uncrewed spacecraft have also been sent to all the planets of the Solar System.

Suborbital spaceflight is the fastest of the existing and planned transport systems from a place on Earth to a distant "other place" on Earth. Faster transport could be achieved through part of a low Earth orbit or by following that trajectory even faster, using the propulsion of the rocket to steer it.

Elements

[edit]

Infrastructure

[edit]

Main article: Infrastructure

Bridges, such as Golden Gate Bridge, allow roads and railways to cross bodies of water.

Bridges, such as Golden Gate Bridge, allow roads and railways to cross bodies of water.

Tunnels, such as the Tampere Tunnel, allow traffic to pass underground or through rock formations.

Tunnels, such as the Tampere Tunnel, allow traffic to pass underground or through rock formations.

Infrastructure is the fixed installations that allow a vehicle to operate. It consists of a roadway, a terminal, and facilities for parking and maintenance. For rail, pipeline, road, and cable transport, the entire way the vehicle travels must be constructed. Air and watercraft are able to avoid this, since the airway and seaway do not need to be constructed. However, they require fixed infrastructure at terminals.

Terminals such as airports, ports, and stations, are locations where passengers and freight can be transferred from one vehicle or mode to another. For passenger transport, terminals are integrating different modes to allow riders, who are interchanging between modes, to take advantage of each mode's benefits. For instance, airport rail links connect airports to the city centres and suburbs. The terminals for automobiles are parking lots, while buses and coaches can operate from simple stops. For freight, terminals act as transshipment points, though some cargo is transported directly from the point of production to the point of use.

The financing of infrastructure can either be public or private. Transport is often a natural monopoly and a necessity for the public; roads, and in some countries railways and airports, are funded through taxation. New infrastructure projects can have high costs and are often financed through debt. Many infrastructure owners, therefore, impose usage fees, such as landing fees at airports or toll plazas on roads. Independent of this, authorities may impose taxes on the purchase or use of vehicles. Because of poor forecasting and overestimation of passenger numbers by planners, there is frequently a benefits shortfall for transport infrastructure projects.[15]

Means of transport

[edit]

Animals

[edit]

Animals used in transportation include pack animals and riding animals.

Vehicles

[edit]

Main article: Vehicle

A Fiat Uno in 2018

A Fiat Uno in 2018

Customized motorcycle to maximize load capacity. Mobility is important for motorcycles, which are primarily used for transporting light cargo in urban areas.

Customized motorcycle to maximize load capacity. Mobility is important for motorcycles, which are primarily used for transporting light cargo in urban areas.

A vehicle is a non-living device that is used to move people and goods. Unlike the infrastructure, the vehicle moves along with the cargo and riders. Unless being pulled/pushed by a cable or muscle-power, the vehicle must provide its own propulsion; this is most commonly done through a steam engine, combustion engine, electric motor, jet engine, or rocket, though other means of propulsion also exist. Vehicles also need a system of converting the energy into movement; this is most commonly done through wheels, propellers, and pressure.

Vehicles are most commonly staffed by a driver. However, some systems, such as people movers and some rapid transits, are fully automated. For passenger transport, the vehicle must have a compartment, seat, or platform for the passengers. Simple vehicles, such as automobiles, bicycles, or simple aircraft, may have one of the passengers as a driver. Recently, the progress related to the Fourth Industrial Revolution has brought a lot of new emerging technologies for transportation and automotive fields such as Connected Vehicles and Autonomous Driving. These innovations are said to form future mobility, but concerns remain on safety and cybersecurity, particularly concerning connected and autonomous mobility.[16]

Operation

[edit]

Incheon International Airport, South Korea

Incheon International Airport, South Korea

Private transport is only subject to the owner of the vehicle, who operates the vehicle themselves. For public transport and freight transport, operations are done through private enterprise or by governments. The infrastructure and vehicles may be owned and operated by the same company, or they may be operated by different entities. Traditionally, many countries have had a national airline and national railway. Since the 1980s, many of these have been privatized. International shipping remains a highly competitive industry with little regulation, but ports can be public-owned.

Policy

[edit]

Further information: List of ministries of transport by country and Traffic management

|

|

This section is missing information about most of what constitutes official traffic management and planning, how it integrates with other fields of politics and how it is enforced. Please expand the section to include this information. Further details may exist on the talk page. (December 2021)

|

As the population of the world increases, cities grow in size and population—according to the United Nations, 55% of the world's population live in cities, and by 2050 this number is expected to rise to 68%.[19] Public transport policy must evolve to meet the changing priorities of the urban world.[20] The institution of policy enforces order in transport, which is by nature chaotic as people attempt to travel from one place to another as fast as possible. This policy helps to reduce accidents and save lives.

Functions

[edit]

Relocation of travelers and cargo are the most common uses of transport. However, other uses exist, such as the strategic and tactical relocation of armed forces during warfare, or the civilian mobility construction or emergency equipment.

Passenger

[edit]

Main articles: Travel and Public transit

A local transit bus operated by ACTION in Canberra, Australia

A local transit bus operated by ACTION in Canberra, Australia

Passenger transport, or travel, is divided into public and private transport. Public transport is scheduled services on fixed routes, while private is vehicles that provide ad hoc services at the riders desire. The latter offers better flexibility, but has lower capacity and a higher environmental impact. Travel may be as part of daily commuting or for business, leisure, or migration.

Short-haul transport is dominated by the automobile and mass transit. The latter consists of buses in rural and small cities, supplemented with commuter rail, trams, and rapid transit in larger cities. Long-haul transport involves the use of the automobile, trains, coaches, and aircraft, the last of which have become predominantly used for the longest, including intercontinental, travel. Intermodal passenger transport is where a journey is performed through the use of several modes of transport; since all human transport normally starts and ends with walking, all passenger transport can be considered intermodal. Public transport may also involve the intermediate change of vehicle, within or across modes, at a transport hub, such as a bus or railway station.

Taxis and buses can be found on both ends of the public transport spectrum. Buses are the cheapest mode of transport but are not necessarily flexible, and taxis are very flexible but more expensive. In the middle is demand-responsive transport, offering flexibility whilst remaining affordable.

International travel may be restricted for some individuals due to legislation and visa requirements.

Medical

[edit]

An ambulance from World War I

An ambulance from World War I

An ambulance is a vehicle used to transport people from or between places of treatment,[21] and in some instances will also provide out-of-hospital medical care to the patient. The word is often associated with road-going "emergency ambulances", which form part of emergency medical services, administering emergency care to those with acute medical problems.

Air medical services is a comprehensive term covering the use of air transport to move patients to and from healthcare facilities and accident scenes. Personnel provide comprehensive prehospital and emergency and critical care to all types of patients during aeromedical evacuation or rescue operations, aboard helicopters, propeller aircraft, or jet aircraft.[22][23]

Freight

[edit]

Main article: Shipping

A bulk carrier, BW Fjord

A bulk carrier, BW Fjord

Freight transport, or shipping, is a key in the value chain in manufacturing. With increased specialization and globalization, production is being located further away from consumption, rapidly increasing the demand for transport. Transport creates place utility by moving the goods from the place of production to the place of consumption.[26] While all modes of transport are used for cargo transport, there is high differentiation between the nature of the cargo transport, in which mode is chosen. Logistics refers to the entire process of transferring products from producer to consumer, including storage, transport, transshipment, warehousing, material-handling, and packaging, with associated exchange of information. Incoterm deals with the handling of payment and responsibility of risk during transport.

Freight train with shipping containers in the United Kingdom

Freight train with shipping containers in the United Kingdom

Containerization, with the standardization of ISO containers on all vehicles and at all ports, has revolutionized international and domestic trade, offering a huge reduction in transshipment costs. Traditionally, all cargo had to be manually loaded and unloaded into the haul of any ship or car; containerization allows for automated handling and transfer between modes, and the standardized sizes allow for gains in economy of scale in vehicle operation. This has been one of the key driving factors in international trade and globalization since the 1950s.

Bulk transport is common with cargo that can be handled roughly without deterioration; typical examples are ore, coal, cereals, and petroleum. Because of the uniformity of the product, mechanical handling can allow enormous quantities to be handled quickly and efficiently. The low value of the cargo combined with high volume also means that economies of scale become essential in transport, and gigantic ships and whole trains are commonly used to transport bulk. Liquid products with sufficient volume may also be transported by pipeline.

Air freight has become more common for products of high value; while less than one percent of world transport by volume is by airline, it amounts to forty percent of the value. Time has become especially important in regards to principles such as postponement and just-in-time within the value chain, resulting in a high willingness to pay for quick delivery of key components or items of high value-to-weight ratio. In addition to mail, common items sent by air include electronics and fashion clothing.

Industry

[edit]

Main article: Transport industry

Impact

[edit]

Main article: Sustainable transport

Economic

[edit]

Main article: Transport economics

Transport is a key component of growth and globalization, such as in Seattle, Washington, United States.

Transport is a key component of growth and globalization, such as in Seattle, Washington, United States.

Transport is a key necessity for specialization—allowing production and consumption of products to occur at different locations. Throughout history, transport has been a spur to expansion; better transport allows more trade and a greater spread of people. Economic growth has always been dependent on increasing the capacity and rationality of transport. But the infrastructure and operation of transport have a great impact on the land, and transport is the largest drainer of energy, making transport sustainability a major issue.

Due to the way modern cities and communities are planned and operated, a physical distinction between home and work is usually created, forcing people to transport themselves to places of work, study, or leisure, as well as to temporarily relocate for other daily activities. Passenger transport is also the essence of tourism, a major part of recreational transport. Commerce requires the transport of people to conduct business, either to allow face-to-face communication for important decisions or to move specialists from their regular place of work to sites where they are needed.

In lean thinking, transporting materials or work in process from one location to another is seen as one of the seven wastes (Japanese term: muda) which do not add value to a product.[33]

Planning

[edit]

Main article: Transport planning

Transport planning allows for high use and less impact regarding new infrastructure. Using models of transport forecasting, planners are able to predict future transport patterns. On the operative level, logistics allows owners of cargo to plan transport as part of the supply chain. Transport as a field is also studied through transport economics, a component for the creation of regulation policy by authorities. Transport engineering, a sub-discipline of civil engineering, must take into account trip generation, trip distribution, mode choice, and route assignment, while the operative level is handled through traffic engineering.

The engineering of this roundabout in Bristol, United Kingdom, attempts to make traffic flow free-moving.

The engineering of this roundabout in Bristol, United Kingdom, attempts to make traffic flow free-moving.

Because of the negative impacts incurred, transport often becomes the subject of controversy related to choice of mode, as well as increased capacity. Automotive transport can be seen as a tragedy of the commons, where the flexibility and comfort for the individual deteriorate the natural and urban environment for all. Density of development depends on mode of transport, with public transport allowing for better spatial use. Good land use keeps common activities close to people's homes and places higher-density development closer to transport lines and hubs, to minimize the need for transport. There are economies of agglomeration. Beyond transport, some land uses are more efficient when clustered. Transport facilities consume land, and in cities pavement (devoted to streets and parking) can easily exceed 20 percent of the total land use. An efficient transport system can reduce land waste.

Too much infrastructure and too much smoothing for maximum vehicle throughput mean that in many cities there is too much traffic and many—if not all—of the negative impacts that come with it. It is only in recent years that traditional practices have started to be questioned in many places; as a result of new types of analysis which bring in a much broader range of skills than those traditionally relied on—spanning such areas as environmental impact analysis, public health, sociology, and economics—the viability of the old mobility solutions is increasingly being questioned.

Environment

[edit]

Global greenhouse gas emissions from transportation:[34]

Cars (40%)

Trucks (34%)

Planes (11%)

Boats (11%)

Trains (4%)

Main article: Environmental impact of transport

Traffic congestion persists in São Paulo, Brazil, despite the no-drive days based on license numbers.

Traffic congestion persists in São Paulo, Brazil, despite the no-drive days based on license numbers.

Transport is a major use of energy and burns most of the world's petroleum. This creates air pollution, including nitrous oxides and particulates, and is a significant contributor to global warming through emission of carbon dioxide,[35] for which transport is the fastest-growing emission sector.[36] By sub-sector, road transport is the largest contributor to global warming.[37] Environmental regulations in developed countries have reduced individual vehicles' emissions; however, this has been offset by increases in the numbers of vehicles and in the use of each vehicle.[35] Some pathways to reduce the carbon emissions of road vehicles considerably have been studied.[38][39] Energy use and emissions vary largely between modes, causing environmentalists to call for a transition from air and road to rail and human-powered transport, as well as increased transport electrification and energy efficiency.

Other environmental impacts of transport systems include traffic congestion and automobile-oriented urban sprawl, which can consume natural habitat and agricultural lands. By reducing transport emissions globally, it is predicted that there will be significant positive effects on Earth's air quality, acid rain, smog, and climate change.[40]

While electric cars are being built to cut down CO2 emission at the point of use, an approach that is becoming popular among cities worldwide is to prioritize public transport, bicycles, and pedestrian movement. Redirecting vehicle movement to create 20-minute neighbourhoods[41] that promotes exercise while greatly reducing vehicle dependency and pollution. Some policies are levying a congestion charge[42] to cars for travelling within congested areas during peak time.

Airplane emissions change depending on the flight distance. It takes a lot of energy to take off and land, so longer flights are more efficient per mile traveled. However, longer flights naturally use more fuel in total. Short flights produce the most CO2 per passenger mile, while long flights produce slightly less.[43][44] Things get worse when planes fly high in the atmosphere.[45][46] Their emissions trap much more heat than those released at ground level. This isn't just because of CO2, but a mix of other greenhouse gases in the exhaust.[47][48] City buses produce about 0.3 kg of CO2 for every mile traveled per passenger. For long-distance bus trips (over 20 miles), that pollution drops to about 0.08 kg of CO2 per passenger mile.[49][43] On average, commuter trains produce around 0.17 kg of CO2 for each mile traveled per passenger. Long-distance trains are slightly higher at about 0.19 kg of CO2 per passenger mile.[49][43][50] The fleet emission average for delivery vans, trucks and big rigs is 10.17 kg (22.4 lb) CO2 per gallon of diesel consumed. Delivery vans and trucks average about 7.8 mpg (or 1.3 kg of CO2 per mile) while big rigs average about 5.3 mpg (or 1.92 kg of CO2 per mile).[51][52]

Sustainable development

[edit]

The United Nations first formally recognized the role of transport in sustainable development in the 1992 United Nations Earth summit. In the 2012 United Nations World Conference, global leaders unanimously recognized that transport and mobility are central to achieving the sustainability targets. In recent years, data has been collected to show that the transport sector contributes to a quarter of the global greenhouse gas emissions, and therefore sustainable transport has been mainstreamed across several of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, especially those related to food, security, health, energy, economic growth, infrastructure, and cities and human settlements. Meeting sustainable transport targets is said to be particularly important to achieving the Paris Agreement.[53]

There are various Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that are promoting sustainable transport to meet the defined goals. These include SDG 3 on health (increased road safety), SDG 7 on energy, SDG 8 on decent work and economic growth, SDG 9 on resilient infrastructure, SDG 11 on sustainable cities (access to transport and expanded public transport), SDG 12 on sustainable consumption and production (ending fossil fuel subsidies), and SDG 14 on oceans, seas, and marine resources.[54]

History

[edit]

Main article: History of transport

Further information: Timeline of transportation technology

Bronocice pot with the earliest known image of a wheeled vehicle in the world, found in Poland

Bronocice pot with the earliest known image of a wheeled vehicle in the world, found in Poland

A bullock team hauling wool in Australia

A bullock team hauling wool in Australia

Natural

[edit]

Humans' first ways to move included walking, running, and swimming. The domestication of animals introduced a new way to lay the burden of transport on more powerful creatures, allowing the hauling of heavier loads, or humans riding animals for greater speed and duration. Inventions such as the wheel and the sled (U.K. sledge) helped make animal transport more efficient through the introduction of vehicles.

The first forms of road transport involved animals, such as horses (domesticated in the 4th or the 3rd millennium BCE), oxen (from about 8000 BCE),[55] or humans carrying goods over dirt tracks that often followed game trails.

Water transport

[edit]

Water transport, including rowed and sailed vessels, dates back to time immemorial and was the only efficient way to transport large quantities or over large distances prior to the Industrial Revolution. The first watercraft were canoes cut out from tree trunks. Early water transport was accomplished with ships that were either rowed or used the wind for propulsion, or a combination of the two. The importance of water has led to most cities that grew up as sites for trading being located on rivers or on the sea-shore, often at the intersection of two bodies of water.

Mechanical

[edit]

Until the Industrial Revolution, transport remained slow and costly, and production and consumption gravitated as close to each other as feasible.[citation needed] The Industrial Revolution in the 19th century saw several inventions fundamentally change transport. With telegraphy, communication became instant and independent of the transport of physical objects. The invention of the steam engine, closely followed by its application in rail transport, made land transport independent of human or animal muscles. Both speed and capacity increased, allowing specialization through manufacturing being located independently of natural resources. The 19th century also saw the development of the steam ship, which sped up global transport.

With the development of the combustion engine and the automobile around 1900, road transport became more competitive again, and mechanical private transport originated. The first "modern" highways were constructed during the 19th century[citation needed] with macadam. Later, tarmac and concrete became the dominant paving materials.

The Wright brothers' first flight in 1903

The Wright brothers' first flight in 1903

In 1903 the Wright brothers demonstrated the first successful controllable airplane, and after World War I (1914–1918) aircraft became a fast way to transport people and express goods over long distances.

After World War II (1939–1945) the automobile and airlines took higher shares of transport, reducing rail and water to freight and short-haul passenger services. Scientific spaceflight began in the 1950s, with rapid growth until the 1970s, when interest dwindled. In the 1950s the introduction of containerization gave massive efficiency gains in freight transport, fostering globalization. International air travel became much more accessible in the 1960s with the commercialization of the jet engine. Along with the growth in automobiles and motorways, rail and water transport declined in relative importance. After the introduction of the Shinkansen in Japan in 1964, high-speed rail in Asia and Europe started attracting passengers on long-haul routes away from the airlines.

Early in U.S. history,[when?] private joint-stock corporations owned most aqueducts, bridges, canals, railroads, roads, and tunnels. Most such transport infrastructure came under government control in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, culminating in the nationalization of inter-city passenger rail-service with the establishment of Amtrak. Recently,[when?] however, a movement to privatize roads and other infrastructure has gained some[quantify] ground and adherents.[58]

See also

[edit]

Transport portal

Transport portal

- Car-free movement

- Energy efficiency in transport

- Environmental impact of aviation

- Free public transport

- Green transport hierarchy

- Health and environmental impact of transport

- Health impact of light rail systems

- IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Society

- Journal of Transport and Land Use

- List of emerging transportation technologies

- Outline of transport

- Personal rapid transit

- Public transport

- Public transport accessibility level

- Rail transport by country

- Speed record

- Taxicabs by country

- Transport divide

- Transportation engineering

References

[edit]

- ^

Crawford, Amy (2021-10-25). "Could flying electric 'air taxis' help fix urban transportation?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2021-11-19. Retrieved 2021-11-19.

- ^ Swine flu prompts EU warning on travel to US Archived 2015-09-26 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian. April 28, 2009.

- ^ "Major Roads of the United States". United States Department of the Interior. 2006-03-13. Archived from the original on 13 April 2007. Retrieved 24 March 2007.

- ^ "Road Infrastructure Strategic Framework for South Africa". National Department of Transport (South Africa). Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 24 March 2007.

- ^ "What is the difference between a road and a street?". Word FAQ. Lexico Publishing Group. 2007. Archived from the original on 5 April 2007. Retrieved 24 March 2007.

- ^ Harvey, Fiona (2020-03-05). "One in five Europeans exposed to harmful noise pollution – study". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2020-03-05. Retrieved 2020-03-05.

- ^ The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) 2007, pp. x, 32.

- ^ Flyvbjerg, Bent; Skamris Holm, Mette K.; Buhl, Søren L. (2005-06-30). "How (In)accurate Are Demand Forecasts in Public Works Projects?: The Case of Transportation". Journal of the American Planning Association. 71 (2): 131–146. arXiv:1303.6654. doi:10.1080/01944360508976688. ISSN 0194-4363.

- ^ Hamid, Umar Zakir Abdul; et al. (2021). "Facilitating a Reliable, Feasible, and Comfortable Future Mobility". SAE International Journal of Connected and Automated Vehicles. 4 (1). Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- ^ Meredith, Sam (2018-05-17). "Two-thirds of global population will live in cities by 2050, UN says". CNBC. Archived from the original on 2020-11-12. Retrieved 2018-11-20.

- ^ Jones, Peter (July 2014). "The evolution of urban mobility: The interplay of academic and policy perspectives". IATSS Research. 38: 7–13. doi:10.1016/j.iatssr.2014.06.001.

- ^ Skinner, Henry Alan. 1949, "The Origin of Medical Terms". Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins

- ^ Branas CC, MacKenzie EJ, Williams JC, Schwab CW, Teter HM, Flanigan MC, et al. (2005). "Access to trauma centers in the United States". JAMA. 293 (21): 2626–2633. doi:10.1001/jama.293.21.2626. PMID 15928284.

- ^ Burney RE, Hubert D, Passini L, Maio R (1995). "Variation in air medical outcomes by crew composition: a two-year follow-up". Ann Emerg Med. 25 (2): 187–192. doi:10.1016/s0196-0644(95)70322-5. PMID 7832345.

- ^ McLeod, Sam; Curtis, Carey (2020-03-14). "Understanding and Planning for Freight Movement in Cities: Practices and Challenges". Planning Practice & Research. 35 (2): 201–219. doi:10.1080/02697459.2020.1732660. ISSN 0269-7459. S2CID 214463529. Archived from the original on 2022-07-30. Retrieved 2021-01-14.

- ^ EKU Online, The Seven Wastes of Lean Manufacturing Archived 2023-03-07 at the Wayback Machine, Eastern Kentucky University, accessed 6 March 2023

- ^ International Council on Clean Transportation, A world of thoughts on Phase 2 Archived 2018-11-19 at the Wayback Machine, 16 September 2016 (page visited on 18 November 2018).

- ^ a b Fuglestvet; et al. (2007). "Climate forcing from the transport sectors" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (2). Center for International Climate and Environmental Research: 454–458. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105..454F. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702958104. PMC 2206557. PMID 18180450. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-06-25. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ^ Worldwatch Institute (16 January 2008). "Analysis: Nano Hypocrisy?". Archived from the original on 13 October 2013. Retrieved 17 January 2008.

- ^ Jan Fuglestvedt; et al. (Jan 15, 2008). "Climate forcing from the transport sectors" (PDF). PNAS. 105 (2): 454–458. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105..454F. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702958104. PMC 2206557. PMID 18180450. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 4, 2018. Retrieved November 20, 2018.

- ^ "Claverton-Energy.com". Claverton-Energy.com. 2009-02-17. Archived from the original on 2021-03-18. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ^ Data on the barriers and motivators to more sustainable transport behaviour is available in the UK Department for Transport study "Climate Change and Transport Choices Archived 2011-05-30 at the Wayback Machine" published in December 2010.

- ^ Environment Canada. "Transportation". Archived from the original on July 13, 2007. Retrieved 30 July 2008.

- ^ Planning (2020-09-09). "20-minute neighbourhoods". Planning. Archived from the original on 2021-09-20. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ "Congestion Charge (Official)". Transport for London. Archived from the original on 2021-03-09. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ a b c "How We Calculate Your Carbon Footprint". Archived from the original on 2012-01-03. Retrieved 2011-12-29.

- ^ "[SafeClimate] measuring and reporting | tools". Archived from the original on 2008-03-27. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

- ^ I, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Working Group (1995-05-04). Climate Change 1994: Radiative Forcing of Climate Change and an Evaluation of the IPCC 1992 IS92 Emission Scenarios. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-55962-1.

- ^ Dempsey, Paul Stephen; Jakhu, Ram S. (2016-07-15). Routledge Handbook of Public Aviation Law. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-29775-0.

- ^ Schumann, Ulrich (2011). "American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Potential to reduce the climate impact of aviation by flight level changes" (PDF). Retrieved 2022-06-30.

- ^ Lee D.S., Pitari G., Grewe V., Gierens K., Penner J.E., Petzold A., Prather M.J., Schumann U., Bais A., Berntsen T., Iachetti D., Lim L.L., Sausen R. (2010). Transport impacts on atmosphere and climate: Aviation. In – Atmospheric Environment Transport Impacts on Atmosphere and Climate: The ATTICA Assessment Report. 44:37:pp.4678-4734.

- ^ a b "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-01-12. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

cite web: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "'Dramatically more powerful': world's first battery-electric freight train unveiled". the Guardian. 2021-09-16. Retrieved 2021-09-21.

- ^ "403 - Forbidden: Access is denied" (PDF).

- ^ Endresen, Øyvind; Sørgård, Eirik; Sundet, Jostein K.; Dalsøren, Stig B.; Isaksen, Ivar S. A.; Berglen, Tore F.; Gravir, Gjermund (2003-09-16). "Emission from international sea transportation and environmental impact". Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 108 (D17): 4560. Bibcode:2003JGRD..108.4560E. doi:10.1029/2002JD002898. ISSN 2156-2202.

- ^ "Sustainable transport". Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. Archived from the original on 2020-10-09. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ "Sustainable transport at the heart of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)". Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. Archived from the original on 2020-10-15. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ Watts, Martin (1999). Working Oxen. Shire Album. Vol. 342. Princes Risborough, Buckinghamshire: Osprey Publishing. p. 4. ISBN 978-0747804154. Retrieved 2016-02-08.

[...] tamed aurochs became the first domestic oxen. The earliest evidence for domestication is found in the Middle East around ten thousand years ago.

- ^ Winston, Clifford (2010). Last exit: privatization and deregulation of the U.S. transportation system. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 978-0-8157-0473-7. OCLC 635492422.

Bibliography

[edit]

- Bardi, Edward; Coyle, John & Novack, Robert (2006). Management of Transportation. Australia: Thomson South-Western. ISBN 0-324-31443-4. OCLC 62259402.

- Chopra, Sunil & Meindl, Peter (2007). Supply chain management : strategy, planning, and operation (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson. ISBN 978-0-13-208608-0. OCLC 63808135.

- Cooper, Christopher P.; Shepherd, Rebecca (1998). Tourism: Principles and Practice (2nd ed.). Harlow, England: Financial Times Prent. Int. ISBN 978-0-582-31273-9. OCLC 39945061. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- Lay, Maxwell G (1992). Ways of the World: A History of the World's Roads and of the Vehicles that Used Them. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-2691-4. OCLC 804297312.

- Stopford, Martin (1997). Maritime Economics (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-15310-7. OCLC 36824728.

Further reading

[edit]

- McKibben, Bill, "Toward a Land of Buses and Bikes" (review of Ben Goldfarb, Crossings: How Road Ecology Is Shaping the Future of Our Planet, Norton, 2023, 370 pp.; and Henry Grabar, Paved Paradise: How Parking Explains the World, Penguin Press, 2023, 346 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXX, no. 15 (5 October 2023), pp. 30–32. "Someday in the not impossibly distant future, if we manage to prevent a global warming catastrophe, you could imagine a post-auto world where bikes and buses and trains are ever more important, as seems to be happening in Europe at the moment." (p. 32.)

External links

[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Transport.

Look up transport or transportation in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

Wikiquote has quotations related to Transport.

Wikivoyage has travel related information for Transportation.

- Transportation from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- America On the Move Archived 2011-08-05 at the Wayback Machine An online transportation exhibition from the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution

Supply chain performance drivers

| |

- Facilities

- Information

- Inventory

- Pricing

- Sourcing

- Transportation

|

Technology and related concepts

| |

|

|

|

|

Perspectives

|

|

| Criticism |

- Appropriate technology

- Luddite

- Precautionary principle

|

| Ecotechnology |

- Environmental technology

- Sustainable design

|

| Policy & politics |

- Government by algorithm

- Intellectual property

- Persuasive technology

- Science policy

- Strategy of Technology

- Technology assessment

- Technorealism

|

| Progressivism |

- Futures studies

- Technological utopianism

- Technocracy movement

- Technological singularity

- Transhumanism

|

| Studies |

- Diffusion of innovations

- History

- Timeline of historic inventions

- Philosophy

- Social construction of technology

- Technological determinism

- Technology acceptance model

|

|

|

|

|

Related concepts

|

|

| Applied science |

- Agronomy

- Architecture

- Construction

- Engineering

- Forensics

- Forestry

- Logistics

- Medicine

- Mining

- Navigation

- Surveying

|

| Innovation |

- Design

- High tech

- Invention

- Mature technology

- Research and development

- Technological convergence

- Technology lifecycle

|

|

|

|

|

Authority control databases  |

| National |

- Germany

- United States

- Japan

- Latvia

- Israel

|

| Other |

|